The Ides of March, 10-yrs after Bear Stearns can it happen again? Doh!

The World is a curiously circular place. 10-years ago the collapse of Bear Stearns and its subsequent rescue by JP Morgan ushered in the panic stage of the Global Financial Crisis. The cataclysm came 6 months later when Lehman went down. Yesterday, Donald Trump appointed CNBC Commentator Larry Kudlow to Gary Cohn's job as director of the NEC.Kudlow was chief economist of Bear when I joined the firm in the early 1990s.

I'm kind of bemused at Kudlow's appointment, but it proves what an adaptable crow Bear alumni are. Bear was a fantastic place to work. We lacked the glib polish of Goldman Sachs, the white-shoe smoothness of Morgan Stanley, the mighty balance sheets of Citi or JP Morgan, and the depth and range of Merrill, but we were united as the smart yappy mammals snapping round the ankles of the Wall Street dinosaurs. Over the next 10 years we stole a mighty share of their lunches! We did it with aplomb, style and underlying honesty – we were brutally open with our clients: we would succeed by making their deals successful. It was the best of times, and I'm still in touch with many of my clients from these days.

When I was there, the mantra of Ace Greenburg ran the firm – absolute honesty on the trading floor and instant death to anyone skirting the rules. His "Memos from the Chairman" was classic: look after the pennies and the dollars will come, hire PSD graduates: "poor, smart and a deep desire to get rich", and whenever you receive a paperclip in the post, save it up to send back to a client. We calculated not buying paperclips saved Bear about $100 per annum, but, heck, it worked!

The question today is could it all happen again? Bear Stearns was brought down by the same collapse in confidence caused by the mortgage shock that sank so many of other financial institutions. Back in 2007 the banks were loaded to the gills with leveraged product on the back of the "originate to sell" model – RMBS, CDOs and the many leveraged derivatives of these "toxic" investments.

Today? The world has changed.

Draconian capital regulations and the "hunt for yield", (caused by central bank ZIRP and NIRP unconventional monetary policy), means most of the risk is more broadly spread across the whole financial environment. Ultimately all the risks laid off by banks and other originators resides somewhere – in insurance companies, hedge funds, credit funds and our pension savings. Risk does not disappear. It just gets spread around – meaning everyone hurts.

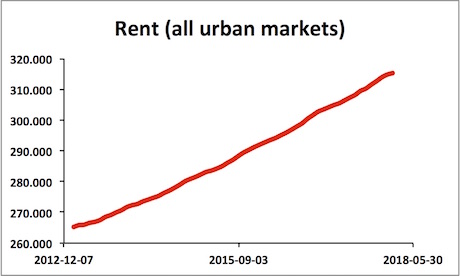

10-years of unconventional monetary policy has changed the investment equation – yields are low and spreads between risk asset classes are compressed to levels that simply don't make risk-sense to those of us who remember the 1980s and 90s. QE has caused inflation – just not where you were looking for it. Its abundantly visible in inflated stock and bond prices. On the other hand – unconventional monetary policy in the form of QE and Low interest rates worked. It kept the financial markets functional.

Now we have synchronous global growth. Estimates all point to continued strength through the next few years. We expect 20% GNP growth over the next 5 years – in theory more than enough to justify current investment valuations. Unconventional is the watchword for the next few years – when else have you seen a nation slashing taxes at the same time as its central bank is considering hiking rates? Or when else has an economy like China successfully moved from export led to a consumption driven model? Populism – the like of which elected Trump – means fiscal policy is back in vogue – infrastructure spend even as the economy recovers?

Yet there are significant risks – liquidity is a major one. Yesterday I read that not a single JGB traded on the Japan bond market. Back when I were young we were trading trillions of yen per day. Now the BOJ owns most of the market. There is no guaranteed liquidity in any bond market – the banks don't take market-making risk if they don't have to. Capital can be arbitraged far more cleanly away from underwriting market risks. Once more let me remind you: the New York Stock Exchange has 27 doors saying "Entrance". There is only one market "Exit".

Then there is geo-politics.

While Trump is getting away with it thus far, at what point do roadblocks arise as he tries to discipline multiple countries from a USA perspective? What are the risks the Chinese stage a Treasury firesale and buyer-strike (Clue: its far less likely than feared as there is literally nowhere else to park their dosh, but its still a fear).

Then there is politics – what are the implications of populism and the long-term threat of increasing income inequality.

These are just the known threats. What about the "no-see-ums"? Every 10-yrs or so something whaps markets like a well wielded wet-kipper across the face. Maybe it's a regional crisis, or a financial instrument class exploding, a taper-tantrum, an investment bubble like dot-coms or tulips, or a deeper than expected bear reversal. Confidence is a very fickle thing.

There are a number of known-market truths – like "countries can't go burst" that have been brutally exposed over the centuries. Maybe it will be European Sovereign Credits? Who knows? What else is wobbling and we just ain't aware of it yet?

What I do know is people who say: "this time its different", are invariably wrong. I shall have a quiet toast to Bear later today.