Fed's monetary policy shift is finally taking hold. It just took a while.

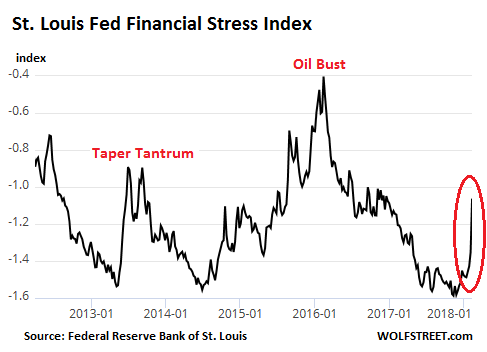

The weekly St. Louis Fed Financial Stress index, released today,

just spiked beautifully. It had been at historic lows back in November,

an expression of ultra-loose financial conditions in the US economy,

dominated by risk-blind investors chasing any kind of yield with a passion,

which resulted in minuscule risk premiums for investors and ultra-low

borrowing costs even for even junk-rated borrows. The index ticked

since then, but in the latest week, ended February 9, something

happened:

The index, which is made up of 18 components (seven interest

rate measures, six yield spreads, and five other indices) had

hit a historic low of -1.6 on November 3, 2017, even as the

Fed had been raising its target range for the federal funds

rate and had started the QE Unwind. It began ticking up late last

year, hit -1.35 a week ago, and now spiked to -1.06.

The chart above shows the spike of the latest week in relationship

to the two-year Oil Bust that saw credit freeze up for junk-rated

energy companies, with the average yield of CCC-or-below-rated

junk bonds soaring to over 20%. Given the size of oil-and-gas

sector debt, energy credits had a large impact on the overall average.

The chart also compares today's spike to the "Taper Tantrum" in the

bond market in 2014 after the Fed suggested that it might actually

taper "QE Infinity," as it had come to be called, out of existence.

This caused yields and risk premiums to spike, as shown by the

Financial Stress index.

This time, it's the other way around: The Fed has been raising rates

like clockwork, and its QE Unwind is accelerating, but for months markets

blithely ignored it. Until suddenly they didn't.

This reaction is visible in the 10-year Treasury yield, which had been

declining for much of last year, despite the Fed's rate hikes, only to

surge late in the year and so far this year.

It's also visible in the stock market, which suddenly experienced a

dramatic bout of volatility and a breathless drop from record highs.

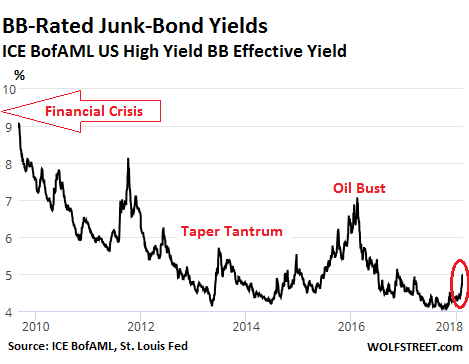

And it is now visible in other measures, including junk-bond yields

that suddenly began surging from historic low levels.

The chart of the ICE BofAML US High Yield BB Effective Yield Index,

via the St. Louis Fed, shows how the average yield of BB-rated

junk bonds surged from around 4.05% last September to 4.98%

now, the highest since November 20, 2016:

But a longer-term chart shows just how low the BB-yield still

is compared to where it had been in the years after the

Financial Crisis, and how much more of a trajectory it might

have ahead:

When yields rise, it means that bond prices are dropping. And

so the selloff that has been hitting the Treasury market is finally

creeping into the riskier parts of the corporate bond market,

which had been in denial of the Fed's efforts to tighten financial

conditions via rate hikes and the QE Unwind.

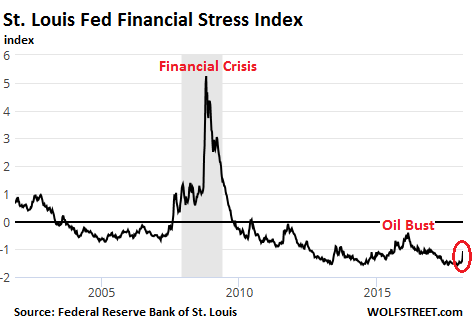

The Financial Stress Index is designed to show a level of zero

for "normal" financial conditions. When these conditions are easy

and when there is less financial stress than normal, the index is

negative. The index turns positive when financial conditions are

tighter than normal.

But at -1.06, it remains below zero. In other words,

financial conditions remain extraordinarily easy. This is clear

in a long-term chart of the index that barely shows the recent spike,

given the magnitude of prior moves:

This is precisely what the Fed wants to accomplish. The market is

just slow in reacting to a shift in monetary policies. But when

it begins to react, the adjustment can be sudden and large. Given

that the Fed wants to "normalize" financial conditions – where

these kinds of measures return to normal levels – there will have

to be quite a bit more tightening in the markets before the market

catches up with the Fed's intentions. And the Fed itself is likely

behind the curve – in which case it too will have to do some

catching up. So these adjustments in yields and prices are coming.

And yesterday's reports didn't help at all.