Economic commentaries, articles and news reflecting my personal views, present trends and trade opportunities. By F. F. F. Russo (PLEASE NO MISUNDERSTANDING: IT'S FREE).

MARKET FLASH:

domenica 31 dicembre 2017

China Launches New Capital Controls: Puts $15,000 Annual Cap On Overseas ATM Withdrawals

The Inescapable Reason Why the Financial System Will Fail

sabato 30 dicembre 2017

How To Defeat Tyranny: "No Shortcuts... No Secret Weapon... Only Indomitable Spirit"

About tiranny:

"Among liberty activists, there is a rather universal consensus on what ails a nation.

We understand that there is a concerted and deliberate effort by the establishment to undermine individual rights and constitutional protections.

We understand that there is a coordinated effort by international financiers to destabilize our economy and siphon wealth from the middle class until it shrivels up and dies.

We understand that there is an organized plan to radicalize the public along ideological lines and pit them against each other.

We understand that geopolitics and regional wars are exploited to distract us from underlying issues.

There is not very much debate over these realities; the evidence is overwhelming.

However, there is constant disagreement among activists on solutions to these problems, and there are several reasons why this conflict persists.

Let's examine them...

Ease Versus Struggle

This is one conflict that I don't think many people recognize or pay much attention to, but it stands as a key weakness that derails effective action. There is a distaste among some liberty activists for the idea of self sacrifice and struggle in achieving freedom. The reality is most fights are won through persistence and force of will; there are no shortcuts to defeating tyranny. There are no secret weapons. There is only indomitable spirit. That's it. It doesn't matter if you have a movement of 100 people or 100 million — any goal is achievable, but only so long as you accept the cost of pain and sacrifice required.

In my years working in the movement I have seen hundreds of poorly conceived silver bullet "solutions" rise to prominence and then fail or disappear entirely. In every case there is a period of overblown excitement while practical strategies are completely ignored. A perfect example would be the current love affair among a subculture of activists with cryptocurrencies. The concept of rebellion on a virtual level is certainly alluring to those who fear real world work and a real world fight. A fantasy of defeating the establishment with ease appeals to those who fear struggle. This is something the powers-that-be take full advantage of.

To defeat concerted technocratic centralization requires nothing less than a willingness to risk everything without the promise of reward. The sooner people realize that there is no easy path to a freer society, the sooner we can act effectively.

Thinking In The Present Versus Thinking Ahead

One truth that I consistently try to point out to activists is that they may never see the benefits of the fighting they do today. They must fight with the expectation that they will not see the light at the end of the tunnel. Successful freedom fighters do not necessarily fight for themselves so much as they fight for the next generation. They fight so that their children can live without tyranny, not only so they can live without tyranny. This idea seems to bewilder some activists, and I blame this on the self serving nature of our society and its addiction to immediate gratification. Even among the best of us, there is a tendency to only plan in the now and seek solutions in the now.

Real rebellion requires long term tactics. Deeply rooted tyrannies are whittled down over time, sometimes over the course of multiple generations. They are not defeated overnight.

Optimism Versus Nihilism

I have seen many liberty analysts attacked as "doom and gloomers," but this accusation is usually wielded by ignorant people with little understanding of how freedom movements function. They do not function on "doom" or "fear porn," but on a healthy dose of reality coupled with the optimistic philosophy that knowledge is power. What the skeptics do not grasp is that we work to comprehend the intricacies of a crisis because we have enough optimism to foresee that the crisis can be stopped, or that something better can be built.

We are not "doom and gloomers," we are actually issuing a rallying cry, because we know that "doom" can in fact be averted.

The real "doom and gloomers" are actually the nihilists — the people that blindly dismiss the possibility of victory. These are the people that do not want to hear about strategies or solutions; they only seek to criticize because they do not have the intelligence to offer up a solution of their own. These are the people who are constantly saying "Yeah, you've told us about the problem, but what are YOU going to do about it," when they should be asking themselves "What am I going to do about it?"

Isolation Versus Community

This is perhaps the defining argument of my years as an analysts and macro-economist, and it is something I continue to fight for to this day. The greatest weakness within the liberty movement and in America as a whole, in my opinion, is the refusal to take the necessity of community seriously. Whether it be because of laziness (ease), because of paranoia or because of too much exposure to Hollywood fantasies of the survival world, many people have adopted the philosophy that preparation for crisis is best done in isolation. In other words, the "lone wolf" mentality.

In almost every historic or modern societal collapse on record, it has been organized communities of people with necessary skill sets that have had the most success in survival. And, it is these communities that offer the most dangerous threat to oligarchies. So, the question becomes, what do you hope to accomplish? Do you seek to survive? Then community is the best possible option. Do you seek to fight back against the encroachment of authoritarianism? Then numerous voluntary communities prepared for disaster are the best weapon.

Does the nail that stands up get hammered down? Possibly. But without community, you ensure that you will always be a nail, and never the hammer. Isolated preparedness is a recipe for failure.

Localization Versus Centralization

As much as liberty activists rail against the problem of centralization, they tend to fall victim to their own centralization schemes. Community only matters when it is VOLUNTARY and within arms reach. This means that internet based communities, while encouraging because they can reveal our true numbers and make us feel as though we are not alone, also tend to centralize our activism within a false framework, isolating us more than uniting us.

A web based community is not a community, just as a web based solution is not a solution. If you are not utilizing the web in part as a tool to build localized community in the real world, or a localized economy in the real world, then you are wasting your time with web activism.

What internet activism does do, unfortunately, is give people a false sense of security, and it prevents them from pursuing real community in the place they live. I have heard on thousands of occasions from activists who claim that "no one around them is awake and aware;" they claim they are alone in the midst of thousands, hundreds of thousands or even millions of people. This is nonsense. In every part of the country I have found liberty-minded people in droves, often all in the same town or city within easy driving distance. And, the people who claim they are alone are usually the people who have never tried to look, or to organize. Why? Because that's hard work, and their virtual community on the internet is so much easier.

The Source Of All Freedom

Beyond the internalized conflicts within liberty movements, there is a defining methodology at stake. The gravitational pull that strengthens communities, the fuel that drives optimism and a respect for the future, the thing that makes us all more than what we seem to be on the surface, the thing that catches authoritarians off guard, is our propensity for courage and human kindness. Without these two things, any fight against tyranny is destined to implode.

Endeavor requires risk, and all risk requires courage (or perhaps stupidity, but courage can often be mistaken as stupidity). The greatest endeavor in the history of mankind is the endeavor to live free. This is one of the few things in the world actually worth fighting or dying for. It only follows that such a fantastic goal would require ultimate risk.

Courage is the willingness to take risks while knowing full well the consequences of failure. In some cases, courage means taking action while knowing that there will be consequences even in success. Sometimes, there are no benefits to the courageous beyond the knowledge that they have benefited others. The fight is not about profit. The fight is not about personal survival. The fight is about something much more. Something difficult to define, but intuitively felt.

Taking terrible risks with the intention of benefiting others, many of them not even born yet, requires human kindness. Kindness in itself can be a form of risk. A self-absorbed sociopath or narcissist will never achieve greatness, because greatness requires actions that are counter-intuitive to self preservation. A person who embraces moral relativism will also never accomplish much for the future. Kindness requires moral resolve, not moral "flexibility."

It is these two characteristics that will help to dissolve the conflicts within liberty activism listed above. It is these two characteristics that defeat tyrants, and so it will be these two characteristics that tyrants will seek to undermine. It is difficult to conquer a people when they are not afraid of sacrifice and when they are not afraid to organize in the real world. It is difficult to isolate people with selfishness when they are driven by the empathy inherent in kindness. ALL solutions, all practical strategies rely on the existence of these two forces within a movement.

As 2017 comes to a close, it is my hope that every liberty activist prepares for more dangerous days ahead. But above all else, their preparations must flow from a foundation of struggle and self sacrifice, foresight and endurance, community and practicality, courage and kindness. If not, then really, what is the point?"

What do you think about it?

Doug Casey On The Coming Financial Crisis: "It's A Gigantic Accident Waiting To Happen"

Justin's note: Earlier this year, Fed Chair Janet Yellen explained how she doesn't think we'll have another financial crisis "in our lifetimes." It's a crazy idea. After all, it feels like the U.S. is long overdue for a major crisis. Below, Doug Casey shares his take on this. It's one of the most important discussions we've had all year.

Justin: Doug, I know you disagree with Yellen. But I'm wondering why she would even say this? Has she lost her mind?

Doug: Listening to the silly woman say that made me think we're truly living in Bizarro World. It's identical in tone to what stock junkies said in 1999 just before the tech bubble burst. She's going to go down in history as the modern equivalent of Irving Fisher, who said "we've reached a permanent plateau of prosperity," in 1929, just before the Great Depression started.

I don't care that some university gave her a Ph.D., and some politicians made her Fed Chair, possibly the second most powerful person in the world. She's ignorant of economics, ignorant of history, and clearly has no judgment about what she says for the record.

Why would she say such a thing? I guess because since she really believes throwing trillions of dollars at the banking system will create prosperity. It started with the $750 billion bailout at the beginning of the last crisis. They've since thrown another $4 trillion at the financial system.

All of that money has flowed into the banking system. So, the banking system has a lot of liquidity at the moment, and she thinks that means the economy is going to be fine.

Justin: Hasn't all that liquidity made the banking system safer?

Doug: No. The whole banking system is screwed-up and unstable. It's a gigantic accident waiting to happen.

People forgot that we now have a fractional reserve banking system. It's very different from a classical banking system. I suspect not one person in 1,000 understands the difference…

Modern banking emerged from the goldsmithing trade of the Middle Ages. Being a goldsmith required a working inventory of precious metal, and managing that inventory profitably required expertise in buying and selling metal and storing it securely. Those capacities segued easily into the business of lending and borrowing gold, which is to say the business of lending and borrowing money.

Most people today are only dimly aware that until the early 1930s, gold coins were used in everyday commerce by the general public. In addition, gold backed most national currencies at a fixed rate of convertibility. Banks were just another business—nothing special. They were distinguished from other enterprises only by the fact they stored, lent, and borrowed gold coins, not as a sideline but as a primary business. Bankers had become goldsmiths without the hammers.

Bank deposits, until quite recently, fell strictly into two classes, depending on the preference of the depositor and the terms offered by banks: time deposits, and demand deposits. Although the distinction between them has been lost in recent years, respecting the difference is a critical element of sound banking practice.

Justin: Can you explain the difference between a time deposit and demand deposit?

Doug: Sure. With a time deposit—a savings account, in essence—a customer contracts to leave his money with the banker for a specified period. In return, he receives a specified fee (interest) for his risk, for his inconvenience, and as consideration for allowing the banker the use of the depositor's money. The banker, secure in knowing he has a specific amount of gold for a specific amount of time, is able to lend it; he'll do so at an interest rate high enough to cover expenses (including the interest promised to the depositor), fund a loan-loss reserve, and if all goes according to plan, make a profit.

A time deposit entails a commitment by both parties. The depositor is locked in until the due date. How could a sound banker promise to give a time depositor his money back on demand and without penalty when he's planning to lend it out?

In the business of accepting time deposits, a banker is a dealer in credit, acting as an intermediary between lenders and borrowers. To avoid loss, bankers customarily preferred to lend on productive assets, whose earnings offered assurance that the borrower could cover the interest as it came due. And they were willing to lend only a fraction of the value of a pledged asset, to ensure a margin of safety for the principal. And only for a limited time—such as against the harvest of a crop or the sale of an inventory. And finally, only to people of known good character—the first line of defense against fraud. Long-term loans were the province of bond syndicators.

That's time deposits.

Justin: And what about demand deposits?

Doug: Demand deposits were a completely different matter.

Demand deposits were so called because, unlike time deposits, they were payable to the customer on demand. These are the basis of checking accounts. The banker doesn't pay interest on the money, because he supposedly never has the use of it; to the contrary, he necessarily charged the depositor a fee for:

Assuming the responsibility of keeping the money safe, available for immediate withdrawal, and…

Administering the transfer of the money if the depositor so chooses, by either writing a check or passing along a warehouse receipt that represents the gold on deposit.

An honest banker should no more lend out demand deposit money than Allied Van and Storage should lend out the furniture you've paid it to store. The warehouse receipts for gold were called banknotes. When a government issued them, they were called currency. Gold bullion, gold coinage, banknotes, and currency together constituted the society's supply of transaction media. But its amount was strictly limited by the amount of gold actually available to people.

Sound principles of banking are identical to sound principles of warehousing any kind of merchandise—whether it's autos, potatoes, or books. Or money. There's nothing mysterious about sound banking. But banking all over the world has been fundamentally unsound since government-sponsored central banks came to dominate the financial system.

Central banks are a linchpin of today's world financial system. By purchasing government debt, banks can allow the state—for a while—to finance its activities without taxation. On the surface, this appears to be a "free lunch." But it's actually quite pernicious and is the engine of currency debasement.

Central banks may seem like a permanent part of the cosmic landscape, but in fact they are a recent invention. The U.S. Federal Reserve, for instance, didn't exist before 1913.

Justin: What changed after 1913?

Doug: In the past, when a bank created too much currency out of nothing, people eventually would notice, and a "bank run" would materialize. But when a central bank authorizes all banks to do the same thing, that's less likely—unless it becomes known that an individual bank has made some really foolish loans.

Central banks were originally justified—especially the creation of the Federal Reserve in the US—as a device for economic stability. The occasional chastisement of imprudent bankers and their foolish customers was an excuse to get government into the banking business. As has happened in so many cases, an occasional and local problem was "solved" by making it systemic and housing it in a national institution. It's loosely analogous to the way the government handles the problem of forest fires: extinguishing them quickly provides an immediate and visible benefit. But the delayed and forgotten consequence of doing so is that it allows decades of deadwood to accumulate. Now when a fire starts, it can be a once-in-a-century conflagration.

Justin: This isn't just a problem in the US, either.

Doug: Right. Banking all over the world now operates on a "fractional reserve" system. In our earlier example, our sound banker kept a 100% reserve against demand deposits: he held one ounce of gold in his vault for every one-ounce banknote he issued. And he could only lend the proceeds of time deposits, not demand deposits. A "fractional reserve" system can't work in a free market; it has to be legislated. And it can't work where banknotes are redeemable in a commodity, such as gold; the banknotes have to be "legal tender" or strictly paper money that can be created by fiat.

The fractional reserve system is why banking is more profitable than normal businesses. In any industry, rich average returns attract competition, which reduces returns. A banker can lend out a dollar, which a businessman might use to buy a widget. When that seller of the widget re-deposits the dollar, a banker can lend it out at interest again. The good news for the banker is that his earnings are compounded several times over. The bad news is that, because of the pyramided leverage, a default can cascade. In each country, the central bank periodically changes the percentage reserve (theoretically, from 100% down to 0% of deposits) that banks must keep with it, according to how the bureaucrats in charge perceive the state of the economy.

Justin: How can a default cascade under the fractional reserve banking system?

Doug: A bank with, say, $1,000 of capital might take in $20,000 of deposits. With a 10% reserve, it will lend out $19,000—but that money is redeposited in the system. Then 90% of that $19,000 is also lent out, and so forth. Eventually, the commercial bank can create hundreds of thousands of loans. If only a small portion of them default, it will wipe out the original $20,000 of deposits—forget about the bank's capital.

That's the essence of the problem. But, in the meantime, before the inevitable happens, the bank is coining money. And all the borrowers are thrilled with having dollars.

Justin: Are there measures in place to prevent bank runs?

Doug: In the US and most other places, protection against runs on banks isn't provided by sound practices, but by laws. In 1934, to restore confidence in commercial banks, the US government instituted the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) deposit insurance in the amount of $2,500 per depositor per bank, eventually raising coverage to today's $250,000. In Europe, €100,000 is the amount guaranteed by the state.

FDIC insurance covers about $9.3 trillion of deposits, but the institution has assets of only $25 billion. That's less than one cent on the dollar. I'll be surprised if the FDIC doesn't go bust and need to be recapitalized by the government. That money—many billions—will likely be created out of thin air by selling Treasury debt to the Fed.

The fractional reserve banking system, with all of its unfortunate attributes, is critical to the world's financial system as it is currently structured. You can plan your life around the fact the world's governments and central banks will do everything they can to maintain confidence in the financial system. To do so, they must prevent a deflation at all costs. And to do that, they will continue printing up more dollars, pounds, euros, yen, and what-have-you.

Justin: It sounds like the banking system is more fragile than it was a decade ago…not stronger.

Doug: Correct. So, Yellen isn't just delusional. As I said before, she has no grasp whatsoever of basic economics.

Her comments remind me of what Ben Bernanke said in May 2007.

We believe the effect of the troubles in the subprime sector on the broader housing market will likely be limited, and we do not expect significant spillovers from the subprime market to the rest of the economy or to the financial system.

A few months later, the entire financial system started to unravel. You would have actually lost a fortune if you listened to Bernanke back then.

Justin: I take it investors shouldn't listen to Yellen, either?

Doug: No. These people are all academics. They don't have any experience in the real world. They've never been in business. They were taught to believe in Keynesian notions. These people have no idea what they're talking about.

The Fed itself serves no useful purpose. It should be abolished.

But people look up to authority figures, and "experts." The average guy has other things on his mind.

Justin: So if Yellen's wrong, what should investors prepare for? How will the coming crisis be different from what we saw in 2007–2008?

Doug: Well, as you know, the Fed has dropped interest rates to near zero. I used to think it was metaphysically impossible for rates to drop below zero. But the European and Japanese central banks have done it.

The other thing they did was create megatons of money out of thin air. This hasn't just happened in the U.S., either. Central banks around the world have printed up trillions of currency units.

How many more can they print at this point? I guess we'll find out. Plus, it's not like these dollars have gone to the retail economy the way they did during the "great inflation" of the '70s. This time they went straight into the financial system. They've created bubbles everywhere.

That's why the next crisis is going to be far more serious than what we saw a decade ago.

Justin: Is there anything the Fed can do to stop this? What would you do if you were running the Fed?

Doug: I've been saying for years that I would abolish the Fed, end the fractional reserve system, and default on the national debt. But would I actually do any of those things? No. I wouldn't. I pity the poor fool who allows the rotten structure to collapse on his watch. Perish the thought of bringing it down in a controlled demolition.

They would literally crucify the person who did this…even if it was good for the economy in the long run. Which it would be.

So, these people are going to keep doing what they've been doing. They're hoping that, if they kick the can down the road, something magic will happen. Maybe friendly aliens will land on the roof of the White House and cure everything.

Justin: So, they can't stop what's coming?

Doug: The whole financial system is on the ragged edge of a collapse at this point.

All these paper currencies all around the world could lose their value together. They're all based on the dollar quite frankly. None of them are tied to any commodity.

They have no value in and of themselves, aside from being mediums of exchange. They're all just floating abstractions, based on nothing.

When we exit the eye of this financial hurricane, and go into the storm's trailing edge, it's going to be something for the history books written in the future.

giovedì 28 dicembre 2017

The Reversal: "Smart Money" Using December Day Sessions To Dump Stocks

Everything changed in December...

For months, the so-called "Smart Money" has been on-board with the incessant rally in US equity markets, buying every dip - no matter how shallow.

However, since the end of November, a very different regime appeared to take hold.

As a reminder, Bloomberg's SMART index is calculated by taking the action of the Dow in two time periods: the first 30 minutes and the close. The first 30 minutes represent emotional buying, driven by greed and fear of the crowd based on good and bad news. There is also a lot of buying on market orders and short covering at the opening. Smart money waits until the end and they very often test the market before by shorting heavily just to see how the market reacts. Then they move in the big way. These heavy hitters also have the best possible information available to them and they do have the edge on all the other market participants. To replicate this index, just start at any given day, subtract the price of the Dow at 10 AM from the previous day's close and add today's closing price. Whenever the Dow makes a high which is not confirmed by the SMFI there is trouble ahead.

What does this mean?

Simple - while the S&P 500 is up for the month, the average day sold off into the close, finishing below the day's open...

In fact, in December ALL of the S&P 500's gains have come from the overnight-session (+2.2%), while the day-session has lost 0.65%...

The Reverse Trickle Down Fake Wealth Effect

The Fed and ECB are going to unwind Trump's tax cut long before it even takes effect. As usual, the dumb money didn't get the memo...

"Each day that goes by is getting closer to a change in the flow in liquidity Jan. 2...There's a $45 billion reduction of QE [quantitative easing asset purchases] from the Fed and ECB Jan. 2."

One of the more "interesting" aspects of this pathetic era is how the narrative magically changes based solely upon which stock market sectors are currently leading. During the deflation rally phase, gamblers hang on every word from Central Banks promising more dopium. Whereas, during the fake reflation phase, gamblers tell us that Central Bank tightening is now magically "bullish". All of this asinine chicanery has been encapsulated here by Z.H.: Are Central Bankers Losing Control?

Parsing the gibberish contained therein, one is struck by the fact that everyone in the economics profession gets to sound smart, even when they offer competing and conflicting theories on the same topic. Which is even more asinine since they are ALL always wrong when it counts the most - at the end of the cycle. They are all caught out at the same time, extrapolating the indefinite asinine into the indefinite future. The notable aspect missing from the above discussion about money printing is any mention whatsoever about 'Conomy, formerly known as "supply" and "demand". That's because we now live in a world of "supply" and "debt". The alchemists of our time have convinced themselves that the addition and substraction of free money is the secret to a strong 'Conomy, regardless of whether we are producing industrial grade machinery or low value-add cappuccinos. We saw this "policy" at work during the last cycle, when about two decades of housing demand was pulled forward into a three year period to paper over mass corporate layoffs. In other words, Central Banks are specialists in subsidizing bankruptcy with short-term liquidity. Liquidity that is the least available when it's most needed.

Which brings me to the point of this post, which is that Central Banks really only have one card left to play which they are now taking off the table - the fake wealth effect. Starting just a few days from now in January, the Fed and ECB will be taking a combined $45 billion of monthly liquidity out of the casino. The most since 2008.

The smart money is prepared for that scenario. The dumb money, not so much.

And those who place their faith in the Plunge Protection Team are apparently the same ones who also believe in Santa Claus...

The Moment The Market Broke: "The Behavior Of Volatility Changed Entirely In 2014"

mercoledì 27 dicembre 2017

Warren Buffett's Favorite Indicator Just Flashed a Major Warning

It is clear stocks are in a massive bubble based on their Price to Sale (P/S valuation).

What about the economy?

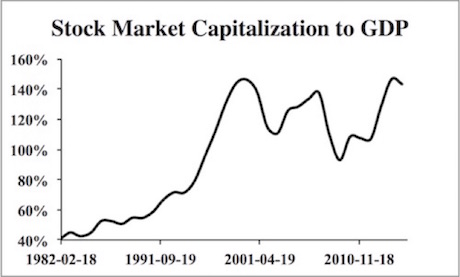

Warren Buffett once famously stated that his favorite means of valuing stock was the stock market capitalization to GDP ratio.

Below is a chart for this metric. As you can see, the stock market today is as overvalued relative to the economy as it was at the peak of the 1999 Tech Mania.

So stocks are overvalued based on the most reliable corporate data point (revenues) and they are also overvalued relative to the economy. Scratch that, they're not overvalued… they're trading at 1999-Tech Bubble insanity levels.

We all remember what came after that...

Fed Cred Dead? From "Definitely Transitory" To "Imperfect Understanding" In One Press Conference

When Janet Yellen spoke at her regular press conference following the FOMC decision in September 2017 to begin reducing the Fed's balance sheet, the Chairman was forced to acknowledge that while the unemployment rate was well below what the central bank's models view as inflationary it hadn't yet shown up in the PCE Deflator.

Of course, this was nothing new since policymakers had been expecting accelerating inflation since 2014.

In the interim, they have tried very hard to stretch the meaning of the word "transitory" into utter meaninglessness; as in supposedly non-economic factors are to blame for this consumer price disparity, but once they naturally dissipate all will be as predicted according to their mandate.

That is, actually, exactly what Ms. Yellen said in September, unusually coloring her assessment some details as to those "transitory" issues:

For quite some time, inflation has been running below the Committee's 2 percent longer-run objective. However, we believe this year's shortfall in inflation primarily reflects developments that are largely unrelated to broader economic conditions. For example, one-off reductions earlier this year in certain categories of prices, such as wireless telephone services, are currently holding down inflation, but these effects should be transitory. Such developments are not uncommon and, as long as inflation expectations remain reasonably well anchored, are not of great concern from a policy perspective because their effects fade away.

Appealing to Verizon's reluctant embrace of unlimited data plans for cellphone service was more than a little desperate on her part. Even if that was the primary reason for the PCE Deflator's continued miss, it still didn't and doesn't necessarily mean what telecoms were up to was some non-economic trivia.

Over the past few years, consumers have been hit with almost regular (not "residual seasonality") shocks to incomes that seem to be increasing in intensity as well as duration. These are, in effect, downturns within a downturn; short run drops or contractions inside an already lost decade. Acceleration of cheap might actually be the most logical of outcomes.

Rather than dismiss these continued problems in favor of fanciful bias towards monetary policy, it was of a far more scientific basis to wonder whether the Fed knows anything about inflation.

A lot has changed in official terms between September and December, which is to say in terms of inflation nothing changed. There is as yet no acceleration in the PCE Deflator (or CPI) that isn't someway connected to oil price effects. In November 2017, the BEA calculates that consumer prices rose by 1.76% year-over-year, up from 1.59% in October as gasoline prices rose 131% (month-over-month, annual rate).

Core rates that strip out energy prices, such as the Dallas Fed's trimmed mean, continue to undershoot and therefore suggest no momentum and zero upon which to base expectations for acceleration. It's not nothing that monetary policy has missed its target for sixty-five out of the last sixty-seven months, and ninety of the past 110 months going back to October 2008 and the botched monetary response to Lehman and everything before it.

Because of all that within the realm of inflation, meaning the monetary system, it has been more than fair or reasonable to ask whether economists really know what they are doing. Up until 2016, that was a question you weren't allowed to consider unless well outside of the mainstream. Since then, more and more policymakers are actually asking of themselves the same idea.

Having failed all throughout 2017, the year almost completely over, Janet Yellen's final press conference for December, then, was subtly changed from the prior one to at least admit that maybe they really don't know – trying hard not to make too much of a big deal about it.

We continue to believe that this year's surprising softness in inflation primarily reflects transitory developments that are largely unrelated to broader economic conditions. As a result, we still expect inflation will move up and stabilize around 2 percent over the next couple of years. Nonetheless, as I've noted previously, our understanding of the forces driving inflation is imperfect.

As a final official act, Yellen downgraded from "definitely transitory" to "imperfect understanding." This matters a great deal, for if their grasp of basic economic factors is this flawed (just an 18% hit rate in nearly 10 years) there's likely far more gone wrong than just the price effects of unlimited wireless data.