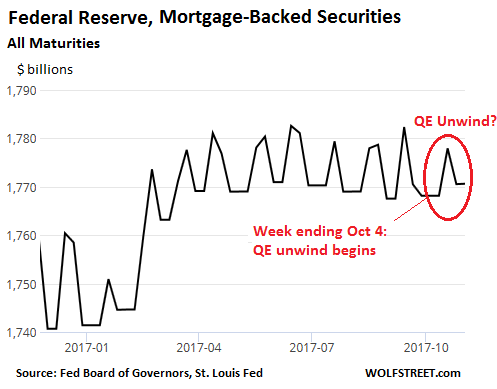

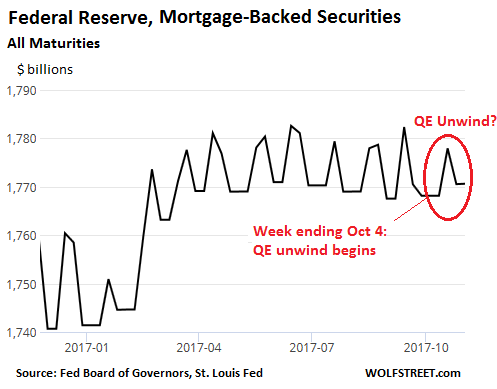

But what's happening with mortgage-backed securities?

Economic commentaries, articles and news reflecting my personal views, present trends and trade opportunities. By F. F. F. Russo (PLEASE NO MISUNDERSTANDING: IT'S FREE).

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

|

William White, chairman of the OECD's review committee and former chief economist of the Bank for International Settlements, who suggests the stresses in the financial system are now "worse than it was in 2007".

Speaking to the UK Telegraph's Ambrose Evans-Pritchard before the start of the World Economic Forum in Davos, White warned that macroeconomic ammunition to fight further economic downturns is essentially "all used up".

"Debts have continued to build up over the last eight years and they have reached such levels in every part of the world that they have become a potent cause for mischief," he told the Telegraph.

"It will become obvious in the next recession that many of these debts will never be serviced or repaid, and this will be uncomfortable for a lot of people who think they own assets that are worth something."

Instead of pondering whether or not bankruptcies will occur, White suggests the only question that needs to be answered is "whether we are able to look reality in the eye and face what is coming in an orderly fashion, or whether it will be disorderly".

White suggests that the US Federal Reserve, fresh from raising interest rates for the first time in nearly a decade in December, is now in a "horrible quandary", carrying the unenviable task of trying to foster an economic recovery while moving away from ultra-easy monetary policy settings.

He believes that easy money policy settings from the Fed, and others such as the European Central Bank and Bank of Japan, simply brought spending forward from the future, creating dangerous cycle that is now losing its potency to spur demand.

"By definition, this means you cannot spend the money tomorrow," he told the Telegraph.

Aside from being demand forward in developed economies, another consequence was to exacerbate asset bubbles in emerging markets such as Asia, pushing asset prices higher on the back of what was - at the time - cheap US dollar denominated debt.

According to Evans-Pritchard, this saw combined public and private debt in emerging markets surge to 185% of GDP, up an alarming 35 percentage points since the peak of the previous credit cycle in 2007.

In OECD nations a debt boom of a similar scale also occurred, taking the overall debt-to-GDP ratio for 34-member group to 265%.

China, at the epicentre of market concerns in recent months, has seen its debt loading climb from 158% of GDP to over 282% over the same period according to analysis from Bank of America-Merrill Lynch.

The chart below reveals the alarming acceleration in the nation's debt loading.

It's little wonder that White, and others, are concerned.

Debt has ballooned while global growth has slowed to a crawl - all at a time when many central banks are already pushing the absolute limits of what stimulus monetary policy can deliver.

If monetary policy, after creating the issue, is no longer in a position to solve it, what can possibly be done to address the situation?

White believes governments hold the key, telling the Telegraph that "they should return to fiscal primacy - call it Keynesian, if you wish - and launch an investment blitz on infrastructure that pays for itself through higher growth".

It's a controversial call, particularly as it would almost certainly require governments to take on even greater amounts of debt.

The International Monetary Fund has warned that the increasing use of exotic financial products tied to equity volatility by investors such as pension funds is creating unknown risks that could result in a severe shock to financial markets.In an interview with the Financial Times Tobias Adrian, director of the Monetary and Capital Markets Department of the IMF, said an increasing appetite for yield was driving investors to look for ways to boost income through complex instruments."The combination of low yields and low volatility facilitates the use of leverage by investors to increase returns, and we have seen rapid growth in some types of products that do this," he saidEquity market volatility has plumbed to its lowest level in a decade, with the Chicago Board Options Exchange's implied volatility index, also known as the Vix, sitting at a level close to 10 compared with an historical average of about 20.