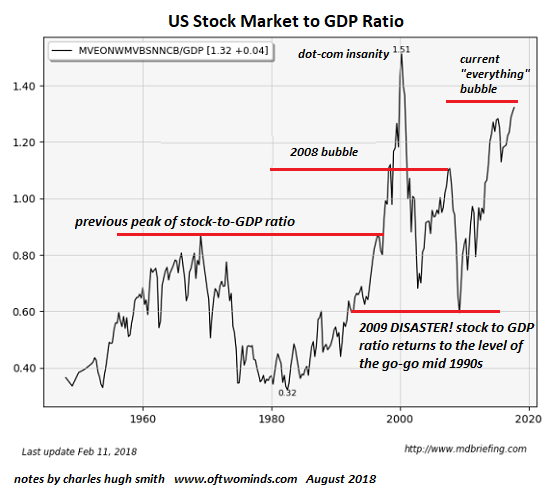

| When the herd thunders off the cliff, most participants are trapped in the stampede.. One of the most perverse consequences of the central banks "saving the world" (i.e. saving banks and the super-wealthy) is the destruction of low-risk investments: we're all speculators now, whether we know it or acknowledge it. The problem is very few of us have the expertise and experience to be successful speculators, i.e. successfully manage treacherously high-risk markets. Here's the choice facing money managers of pension funds and individuals alike: either invest in a safe low-risk asset such as Treasury bonds and lose money every year, as the yield doesn't even match inflation, or accept the extraordinarily high risks of boom-bust bubble assets such as junk bonds, stocks, real estate, etc. The core middle-class asset is the family home. Back in the pre-financialization era (pre-1982), buying a house and paying down the mortgage to build home equity was the equivalent of a savings account, with the added bonus of the potential for modest appreciation if you happened to buy in a desirable region. In the late 1990s, the stable, boring market for mortgages was fully financialized and globalized, turning a relatively safe investment and debt market into a speculative commodity. We all know the results: with the explosion of easy access to unlimited credit via HELOCs (home equity lines of credit), liar loans (no-document mortgages), re-financing, etc., the hot credit-money pouring into housing inflated a stupendous bubble that subsequently popped, as all credit-asset bubbles eventually do, with devastating consequences for everyone who reckoned their success in a rising market was a permanent feature of the era and / or evidence of their financial genius. Highly volatile speculative bubbles are notoriously humbling, even for experienced traders. Buy low and sell high sound easy, but when the herd is running and animal spirits are euphoric, only the most disciplined speculators and the lucky few who have to sell exit near the top of the bubble. The "safety" of investments in housing, commercial real estate, stocks, corporate bonds, emerging markets, etc., is illusory: these are now inherently risky markets, and it's difficult to hedge these risks. (Not many participants knpw how to hedge housing, commercial real estate, etc.) In an environment in which participants have been richly rewarded for believing that "the Fed has our backs," i.e. central banks will never let risk-assets drop because they understand pension funds, insurers, banks, etc. will implode if the risk-asset bubbles pop, few see the need to bother with hedges, as hedges cost money and reduce yields. As a result, few participants are fully hedged. Most participants are buck-naked in terms of exposure to risk, and once the tide goes out we'll find out how few are hedged against bubbles popping. Financial markets are not linear by nature, so predictably rising markets are atypical. Financial markets are intrinsically non-linear, meaning that the dynamics are inter-connected and prone to asymmetric events in which a small input triggers an outsized output such as a crash. In the fantasy world conjured by central bank stimulus, markets never go down and economies never slide into recession. Financial engineering has eradicated risk. But the dynamics interact in ways that can't be controlled. As inflation heats up globally, central banks are being forced to "normalize" interest rates and yields, and political pressure to stop saving banks and the super-wealthy is mounting. All speculative markets deflate, slowly or suddenly, depending on the marginal buyers and sellers. The shakier the marginal participants, the greater the likelihood that the speculative bubble will pop with a suddenness that surprises the vast majority of participants. Take a look at stock valuations as a percentage of GDP, i.e. the real economy: stocks are clearly in a bubble.

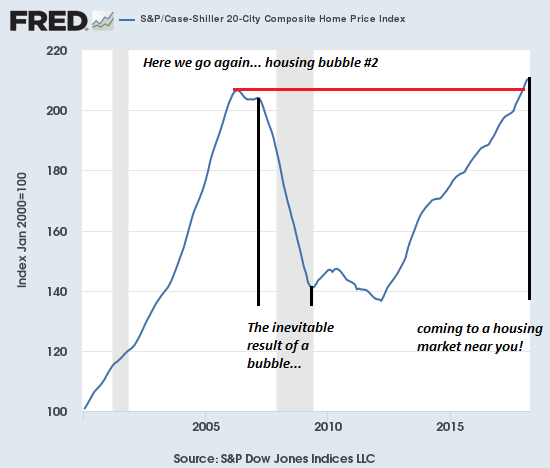

The national Case-Shiller housing price index: bubble.

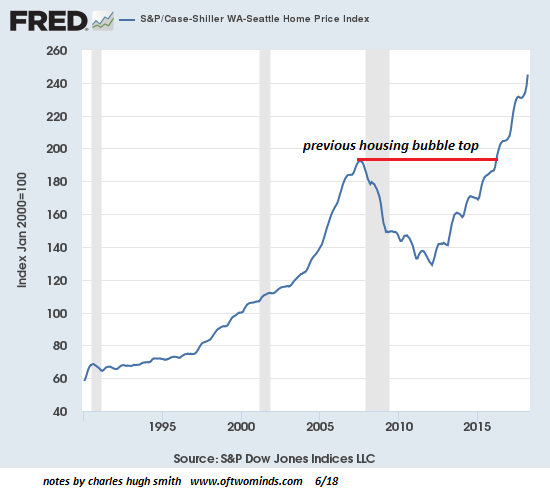

The Seattle Case-Shiller housing price index: super-bubble.

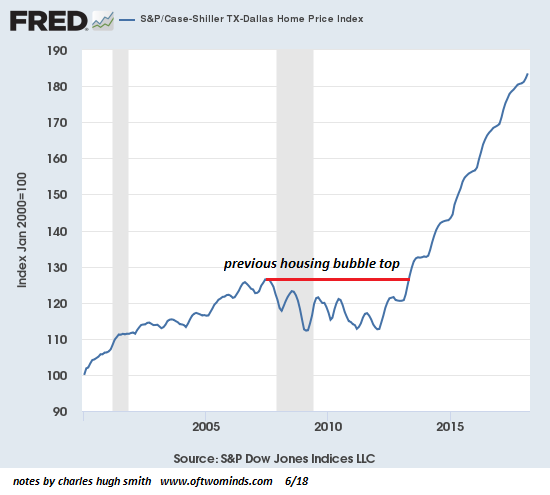

The Dallas Case-Shiller housing price index: super-duper-bubble.

You get the point: virtually every supposedly low-risk asset class is actually a super-risky, super-dangerous bubble. Speculation drives valuations far beyond financial rationality because we're herd animals and unearned gains supercharge our greed, especially when we see all sorts of undeserving people making fortunes for doing nothing but running with the herd. So when the herd thunders off the cliff, most participants are trapped in the stampede. Very few exited far from the cliff, and even fewer will wait patiently for the dust to settle before moving cash into assets. Risk has a knack for hiding in plain sight. Few people look for it, and even fewer recognize it. Only a handful act on it. |