Going back to early CBBs, I've found it useful to caricature the analysis into two distinctly separate systems, the "Real Economy Sphere" and the "Financial Sphere." It's been my long-held view that financial and monetary policy innovations fueled momentous "Financial Sphere" inflation. This financial Bubble has created increasingly systemic maladjustment and structural impairment within both the Real Economy and Financial Spheres. I believe finance today is fundamentally unstable, though the associated acute fragility remains suppressed so long as securities prices are inflating.

[ZH: This week's sudden burst of volatility across all asset-classes highlights this Minskian fragility]

The mortgage finance Bubble period engendered major U.S. structural economic impairment. This became immediately apparent with the collapse of the Bubble. As was the case with previous burst Bubble episodes, the solution to systemic problems was only cheaper "money" in only great quantities. Moreover, it had become a global phenomenon that demanded a coordinated central bank response.

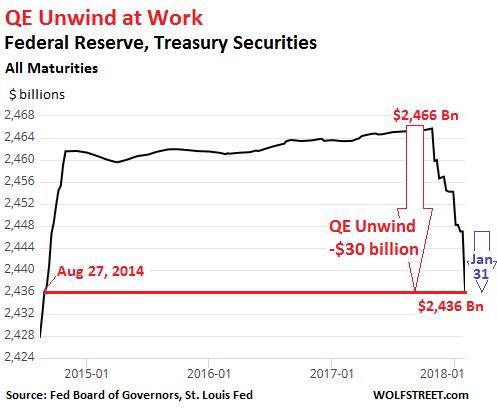

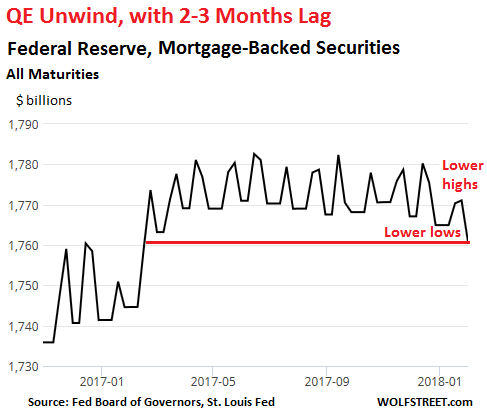

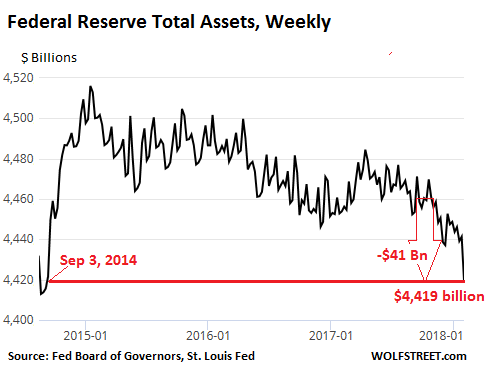

Where has all this led us? Global "Financial Sphere" inflation has been nothing short of spectacular. QE has added an astounding $14 TN to central bank balance sheets globally since the crisis. The Chinese banking system has inflated to an almost unbelievable $38 TN, surging from about $6.0 TN back in 2007. In the U.S., the value of total securities-to-GDP now easily exceeds previous Bubble peaks (1999 and 2007). And since 2008, U.S. non-financial debt has inflated from $35 TN to $49 TN. It has been referred to as a "beautiful deleveraging." It may at this time appear an exquisite monetary inflation, but it's no deleveraging. We'll see how long this beauty endures.

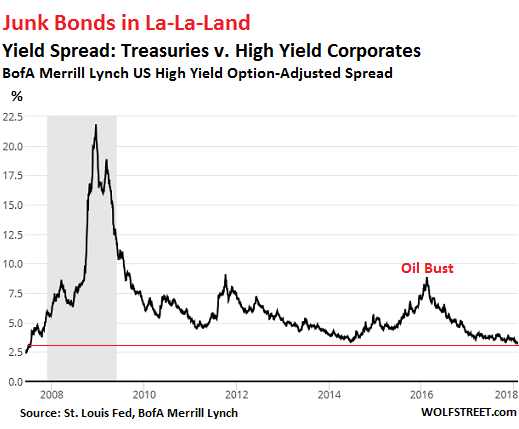

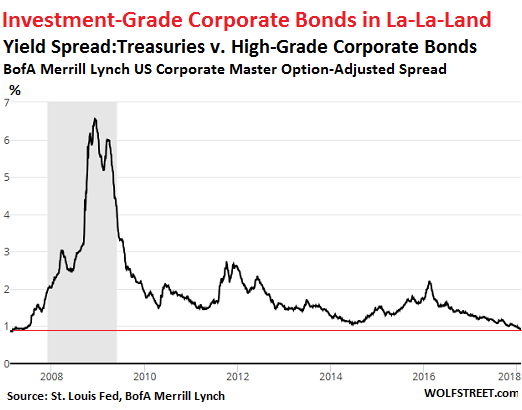

The end result has been way too much "money" slushing around global securities and asset markets – "hot money" of epic proportions. This has led to unprecedented price distortions across asset classes – unparalleled global Bubbles in sovereign debt, corporate Credit, equities and real estate – deeply systemic Bubbles in both (so-called) "risk free" and risk markets. And so long as securities prices are heading higher, it's all widely perceived as a virtually sublime market environment. Yet this could not be further detached from the reality of a dysfunctional "Financial Sphere" of acutely speculative markets fueling precarious Bubbles - all dependent upon unyielding aggressive monetary stimulus.

I have posited that aggressive tax cuts at this late stage of the cycle come replete with unappreciated risks. Global central bankers for far too long stuck with reckless stimulus measures. A powerful inflationary/speculative bias has enveloped asset markets globally. Meanwhile, various inflationary manifestations have taken hold in the global economy, largely masked by relatively contained consumer price aggregates. Meanwhile, global financial markets turned euphoric and speculative blow-off dynamics took hold. A confluence of developments has created extraordinary financial, market, economic, political and geopolitical uncertainties – held at bay by history's greatest Bubble.

Bloomberg: "U.S. Average Hourly Earnings Rose 2.9% Y/Y, Most Since 2009." Average hourly earnings gains have been slowly trending higher for the past several years. Wage gains have now attained decent momentum, which creates uncertainty as to how the tax cuts and associated booming markets will impact compensation gains going forward.

February 2 - Bloomberg (Rich Miller): "As Jerome Powell prepares to take over as chairman of the Federal Reserve on Feb. 5, some of his colleagues are publicly agitating for a radical rethink of the central bank's playbook for guiding monetary policy. Behind the push for reconsideration of the Fed's 2% inflation target: a fear of running out of monetary ammunition in the next recession. With interest rates near historically low levels—and likely to remain that way for the foreseeable future—these officials worry the Fed will have little leeway to aid the economy when a downturn inevitably hits. They argue that revamping the inflation objective beforehand could help counteract that. 'The most important issue on the table right now is that we need to consider the possibility of a new economic normal that forces us to reevaluate our targets,' Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia President Patrick Harker said in a Jan. 5 speech."

"Is the Fed's Inflation Target Kaput?", was the headline from the above Bloomberg article. There is a contingent in the FOMC that would welcome an inflation overshoot above target, believing this would place the Fed in a better position to confront the next downturn. With yields now surging, these inflation doves could be a growing bond market concern.

Interestingly, markets were said to have come under pressure Friday on hawkish headlines from neutral/dovish Dallas Fed President Robert Kaplan: "If We Wait to See Actual Inflation, We'll Be Too Late; We'll Likely Overshoot Full Employment This Year; We Central Bankers Must Be Very Vigilant; Base Case Is For 3 Rate Hikes in 2018, Could Be More."

[ZH: something changed this week]

Are Kaplan's comments to be interpreted bullish or bearish for the struggling bond market? Are bonds under pressure because of heightened concerns for future inflation - or is it instead more because of a fear of tighter monetary policy? Confused by the spike in yields back in 1994, the Fed questioned whether the bond market preferred a slow approach with rate hikes or, instead, more aggressive tightening measures that would keep a lid on inflation.

Just as a carefree Janet Yellen packs her bookcase for the Brookings Institute, the Powell Fed's job has suddenly morphed from easy to challenging. With tax cut stimulus in the pipeline and signs of a backdrop supportive to higher inflation, a growing contingent within the FOMC may view more aggressive tightening measures as necessary support for an increasingly skittish bond market. At the minimum, the backdrop might have central bankers thinking twice before coming hastily to rescue vulnerable stock markets.

...

The marketplace has begun to ponder risk again.

February 1 – Bloomberg (Sarah Ponczek and Lu Wang): "Coordinated selling in stocks and bonds is making life miserable for investors in one of the most popular asset allocation strategies: those lumped together under the rubric of 60/40 mutual funds. Counter to their owners' hope, that pain in one will be assuaged by the other, this week has seen both fixed-income and equities tumbling as concern has built about the pace of Federal Reserve interest rate increases. Funds that blend assets have borne the brunt, suffering their worst weekly performance since Feb 2009."

Stock prices have been going up for a long time – and seemingly straight up for a while now. Bonds, well, they've been in a 30-year bull market. Myriad strategies melding stocks and fixed-income have done exceptionally well. And so long as bonds rally when stocks suffer their occasional (mild and temporary) pullbacks, one could cling to the view that diversified stock/bond holdings were a low risk portfolio strategy (even at inflated prices for both). And for some time now, leveraging a portfolio of stocks and bonds has been pure genius. The above Bloomberg story ran Thursday. By Friday's close, scores of perceived low-risk strategies were probably questioning underlying premises. A day that saw heavy losses in equities, along with losses in Treasuries, corporate Credit and commodities, must have been particularly rough for leveraged "risk parity" strategies.

It's worth noting that the U.S. dollar caught a bid in Friday's "Risk Off" market dynamic. Just when the speculator Crowd was comfortably positioned for dollar weakness (in currencies, commodities and elsewhere), the trade abruptly reverses. It's my view that heightened currency market volatility and uncertainty had begun to impact the general risk-taking and liquidity backdrop. And this week we see the VIX surge to 17.31, the high since the election.

The cost of market risk protection just jumped meaningfully. Past spikes in market volatility were rather brief affairs – mere opportunities to sell volatility (derivatives/options) for fun and hefty profit. I believe markets have now entered a period of heightened volatility. To go along with currency market volatility, there's now significant bond market and policy uncertainty. The premise that Treasuries – and, only to a somewhat lesser extent, corporate Credit – will rally reliably on equity market weakness is now suspect. Indeed, faith that central bankers are right there to backstop the risk markets at the first indication of trouble may even be in some doubt with bond yields rising on inflation concerns. When push comes to shove, central bankers will foremost champion bond markets.

While attention was fixed on U.S. bond yields and equities, it's worth noting developments with another 2018 Theme:

February 2 – Wall Street Journal (Shen Hong): "Chinese stocks had their worst week since 2016, with fresh concerns about Beijing's campaign to cut financial risk and predictions of a slowing economy helping erase half of the market's year-to-date gains in just a few days… Mr. Zhang [chief executive of CYAMLAN Investment] said the increasingly frequent market intervention by the 'national team' to prop up the major indexes could prove counterproductive. 'It's OK to bring in the national team when there's a huge crisis but if it's there everyday, it will create even more jitters,' Mr. Zhang said. 'If you see policemen everywhere, don't you feel less safe?'"

The Shanghai Composite dropped 2.7% this week. Losses would have been headline-making if not for a 2.1% rally off of Friday morning lows.

The Shenzhen Exchange A index sank 6.6% this week, and China's growth stock ChiNext Index was hit 6.3%. The small cap CSI 500 index fell 5.9%, and that was despite a 2.1% rally off Friday's lows (attributed to "national team" buying). Financial stress has been quietly gaining momentum in China, with HNA and small bank liquidity issues the most prominent. As global liquidity tightens, I would expect Chinese Credit issues to be added to a suddenly lengthening list of global concerns.

Unless risk markets can quickly regain upside momentum, I expect "Risk Off" dynamics to gather force. "Risk On" melt-up dynamics were surely fueled by myriad sources of speculative leverage, including derivative strategies (i.e. in-the-money call options). As confirmed this week, euphoric speculative blow-offs are prone to abrupt reversals. Derivative players that were aggressively buying S&P futures to dynamically hedge derivative exposures one day can turn aggressive sellers just a session or two later. And in the event of an unanticipated bout of self-reinforcing de-risking/de-leveraging, it might not take long for the most abundant market liquidity backdrop imaginable to morph into an inhospitable liquidity quandary.

February 1 – Bloomberg (Sarah Ponczek): "When stocks fall, investors typically pull money out of the market. But when U.S. equities suffered their worst two-day slump since May, some traders didn't blink an eye. Exchange-traded funds took in $78.5 billion in January, exceeding the previous monthly record by nearly 30%. ETFs saw close to $4 billion a day in inflows even on the stock market's down days, according to Eric Balchunas, a Bloomberg Intelligence senior ETF analyst…"

Adding January's $79 billion ETF inflow to 2017's record $476 billion puts the 13-month total easily over half a Trillion. If the ETF Complex is hit by significant outflows, it's not clear who will take the other side of the trade. This is especially the case if the hedge funds move to hedge market risk and reduce net long exposures. And let there be no doubt, the leveraged speculators will be following ETF flows like hawks ("predators").

And I'm having difficulty clearing some earlier (Bloomberg) interview comments from my mind:

January 24 – Bloomberg (Nishant Kumar and Erik Schatzker): "Billionaire hedge-fund manager Ray Dalio said that the bond market has slipped into a bear phase and warned that a rise in yields could spark the biggest crisis for fixed-income investors in almost 40 years. 'A 1% rise in bond yields will produce the largest bear market in bonds that we have seen since 1980 to 1981,' Bridgewater Associates founder Dalio said… in Davos…"

Dalio: "'There is a lot of cash on the sidelines'. ... We're going to be inundated with cash, he said. "If you're holding cash, you're going to feel pretty stupid.'"

Here I am, as usual, plugging away late into Friday night. So, who am I to take exception to insight from a billionaire hedge fund genius. But to discuss the possibility of the worst bond bear market since 1981 - and then suggest those holding cash "are going to feel pretty stupid"? Seems to be a disconnect there somewhere. Going forward, I expect stupid cash to outperform scores of brilliant strategies.

The historic "Financial Sphere" Bubble has ensured that ungodly amounts of "money" and leverage have accumulated in The Grand Crowded Trade of Financial Speculation.

And as we detailed earlier - it doesn't get any more crowded that record long equities and record short bonds!