Italy's economic growth is decelerating, which is even more inevitable in view of the country's population decline. It looks as if the Italian business cycle had reached its peak in 2017, with a meagre 1.5% growth rate, and is now receding. Within ten years, Italy will have business cycles with only negative highs and lows. Unemployment is at 10% and it cannot be tackled because Rome is prohibited by the European Union from following the Japanese monetary and fiscal policies to counter the financial fallout as a result of a declining population. Italian academia still believes that replacing the highly-efficient European workforce with Africans will stimulate future economic growth. Italy appears to have been deliberately flooded by Africans, while white workers from Italy are moving to Germany and the Netherlands.

Paolo Savona, the new Italian Minister of Economic Affairs, believes that Germany is executing the 1940 Walther Funk plan. Walther Funk was Director of the Bank of International Settlements and, in 1939, Hitler appointed him as the President of the Reichsbank. Mr Savona laid down his views in a 2012 letter to his German and Italian friends. "The Funk Plan, provided for national currencies to converge into the German mark's area and this is what you would like and have partially achieved," Paolo Savona wrote. "It also envisaged," he continued, "that industrial development only pertained to yourselves and that you would only be accompanied by France, your 'historical' ally, a solution now caused by the common European market and the single currency. The Plan wanted other countries to devote themselves to agriculture and tourist services, something that will happen out of necessity or because of a natural 'calling' and they will lend skilled labour to your leadership project." As it is, Paolo Savona, a representative of the Italian establishment, expressed the feeling of a big part of the Italian elite.

The establishment is divided over how to solve Italy's demographic and economic problems. Matteo Renzi, previous Italian Prime Minister, believed that he could save the country by letting in hundreds of thousands of undocumented Africans. To show that they are committed to repopulate Italy with Africans, the Italian establishment appointed a Congo-born African woman as their Minister for Integration in 2013, a year before the great exodus from Africa kicked off. Italy was on the way to becoming Europe's first black country.

In a democracy it is a ruling class (or to be more precise its factions) that makes political choices and these are later presented to the people to vote for. An alternative policy to Matteo Renzi migration policy was introduced by Lega Nord and the Five-Star Movement. The Italian Minister of the Interior, Mateo Salvini, has challenged the European elites by stopping the endless flood of people from Africa and became incredibly popular. It is easier to halt the influx of people than to pull Italy out of the euro. A break-up of the euro would cause a significant crisis, and nobody knows how it would end, or whether it is manageable. However, the break up of the Sovjet Union and Yugoslavia were also examples of a "currency-union" break up.

To understand how the Italians will solve their ongoing crisis, we have to look at the political and business establishment. The Greek rebellion, led by the maverick Finance Minister Yanous Varoufakis and supported by the majority of the Greek people, ended in Mr Varoufakis being removed from office and the Greek economy destroyed because the minister failed to understand how a democracy functions. He believed it has something to do with the will of the people. He lacked the support of the ruling establishment, so failure was inevitable. Support from some parts, not necessary all, of the economic, academic, financial, juridical, media and security establishment are indispensable. We rightly noticed that both Donald Trump presidency and Brexit were supported by big chunks of US and British ruling elite respectively, whatever the pundits may want you to believe.

The Machiavellian Italian politicians in Rome understand that they have to build a strong opposition in Italy against Europe and Germany. Every crisis has to be blamed on powers outside Rome. The engineered migration crisis, with the support of the Brussels establishment, has backfired, giving Mateo Salvini the opportunity to pitch the Italian people against the European Union, and making him even more popular. According to the latest polls, Salvini's party is gaining in popularity rapidly, with 30% of the votes, while M5S is in decline from 40% to 30%.

A euro exit will not be announced in advance but will be executed overnight the moment nobody expects. If the Italians start to pay their domestic obligations in liras, it will take a while before these are accepted and their value will collapse immediately, so much so that people will then start to withdraw their money from banks. For that reason, the government will take precautions, such as capital control by means of which people will not be allowed to take their money out of the country for a limited period. Unlike Greeks, the Italians will prepare an Italian exit from the euro carefully and secretly.

However, there are not many Italian politicians who dare to take the risk of an outright withdrawal from the European Union and face the consequences except for the Minister of European Affairs Paolo Savono. Mr Savona is now 82 and he has little to lose. He could go down in history as the man who took Italy out of the euro. However, it seems that the financial establishment has ousted Mr Paola Savona after he criticised them for mishandling the ongoing banking crisis and it is not known how much support he still has.

For now, Rome's strategy is to force the Germans to accept relaxed budget rules and allow Italy to introduce a parallel currency. The alternative, Italian withdrawing from the euro will not only result in chaos in Italy but also in Berlin as the consequences for the German financial system are unknown. The Italian budget rules violations will be ignored by the German political establishment who are not capable of preventing any crisis in advance. Angela Merkel will only move when things are already out of control.

If the Italians leave the euro, there will be a discussion about the outstanding debt, denominated in euro's, and there will also be a dispute about the Target2 balance. Target 2 is the real-time gross settlement system for the Eurozone. According to these balance positions, Italy and Spain have a liability from more than 800 billion euros. It is not clear how to interpret these liabilities and who has to pay Germany's balance total of nearly 1 trillion euro.

It is expected that the 2019 Italian budget will reveal whether the government is committed to lowering its debt to GDP levels as is required by the European Stability and Growth Pact or whether it will fulfil its promise to the Italian voters. After Mateo Salvini made good on his promise to stop Africans from flooding Italy, now it is Luigi Di Maio's (the M5S coalition partner's) turn to make good on his promise of a basic income. This basic income is a social security of about 780 euro for all Italians. By implementing this social security program, Italian government spending will rise and provoke the first step to a confrontation with their German counterparts. In August, Luigi Di Maio said that "EU rules can't be excuse to block programs" and "respecting fiscal rules is not Italy's priority" he also announced to an Italian paper that the country's public deficit could exceed the European Union's ceiling of 3 per cent of the gross domestic product next year to fund spending measures promised.

Breaching the budget rules is not a 'big deal' for now. The Italians already violated European banking rules when they rescued a couple of Italian banks in 2016 and 2017 with tax money. It will slowly sink in that Italy will never recover. By next summer, the German establishment will begin to understand that an ever-shrinking population is not only a problem for the sustainability of the public debt, but that it will also erode the Italian bank balance sheets further. The financial market will also ignore the problem for now because Italy has used the ECB bond buyback program to replace its short-term debt for long-term debt. The average maturity of outstanding debt has risen from less than four years in the 1990-1998 period, just before the introduction of the euro, to 6.9 years in 2017. Moreover, nearly 70 per cent of the debt is held by residents, which is amongst the highest in the European Union. For now, Italy does not need the financial market to refinance its old obligation. And for its increasing new debt, it already has an alternative plan: the mini-BOT, a coupon that can be used to pay taxes, state services, and for petrol at stations run by state-controlled oil company ENI. Those who understand money will realise the mini-BOT is a full-blown parallel currency.

The Italian establishment understands that it is the ruling class not the people that manages the country. Whether they leave the euro or not is not up to the populous. When they decide to pull the plug on the euro, they will take care that the people will applaud. After all Machiavelli was an Italian.

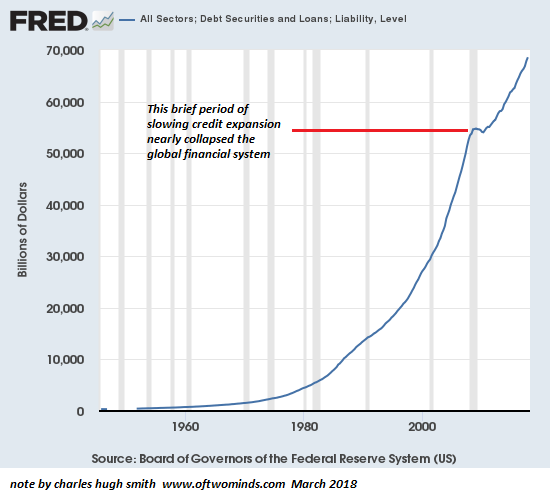

Are we on the verge of another great financial crisis, a devastating recession and a horrific implosion of the global debt bubble? I have been relentlessly warning about the inevitable consequences of our very foolish actions, but now the mainstream media is beginning to sound just like contrarians. The coming crisis is so close now that a lot of them are starting to see it, and of course economic disaster is already a reality for much of the rest of the planet. For years, the mainstream media told us that things would get better, and in a lot of ways we did see some improvement. But now the tone of the mainstream media has become quite ominous, and that is definitely not a positive sign. The following are 8 examples of mainstream media sources warning us of imminent economic disaster…

Are we on the verge of another great financial crisis, a devastating recession and a horrific implosion of the global debt bubble? I have been relentlessly warning about the inevitable consequences of our very foolish actions, but now the mainstream media is beginning to sound just like contrarians. The coming crisis is so close now that a lot of them are starting to see it, and of course economic disaster is already a reality for much of the rest of the planet. For years, the mainstream media told us that things would get better, and in a lot of ways we did see some improvement. But now the tone of the mainstream media has become quite ominous, and that is definitely not a positive sign. The following are 8 examples of mainstream media sources warning us of imminent economic disaster…