During the sell-off, it ignored the whiners on Wall Street.

The fifth month of the QE-Unwind came to a completion with the release this afternoon of the Fed's balance sheet for the week ending February 28. The QE-Unwind is progressing like clockwork. Even during the sell-off in early February, the QE-Unwind never missed a beat.

During QE, the Fed acquired Treasury securities and mortgage-backed securities (MBS) guaranteed by Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and Ginnie Mae. During the QE-Unwind, the Fed is shedding those securities. According to its plan, announced last September, the Fed would reduce its holdings of Treasuries and MBS by no more than:

- $10 billion a month in Q3 2017.

- $20 billion a month in Q1 2018

- $30 billion a month in Q2 2018

- $40 billion a month in Q3 2018

- $50 billion a month in Q4 2018 and continue at this pace.

This would shrink the balance of Treasuries and MBS by up to $420 billion in 2018, by up to an additional $600 billion in 2019 and every year going forward until the Fed decides that the balance sheet has been "normalized" enough — or until something big breaks.

For February, the plan called for shedding up to $20 billion in securities: $12 billion in Treasuries and $8 billion in MBS.

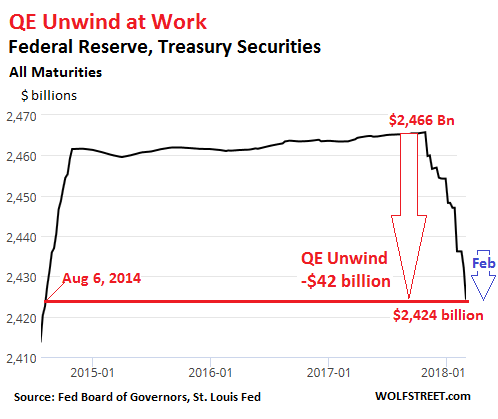

The easy part first: Treasury Securities

On its January 31 balance sheet, the Fed had $2,436 billion of Treasuries; on today's balance sheet, $2,424 billion: a $12 billion drop for February. On target! In total, since the beginning of the QE Unwind, the balance of Treasuries has dropped by $42 billion, to hit the lowest level since August 6, 2014:

In the chart above, the stair-step down movement is a result of the mechanics with which the Fed sheds securities. It does not sell Treauries but allows them to "roll off" when they mature: mid-month and at the end of the month. On February 15, $16.6 billion in Treasuries on the Fed's balance sheet matured; on February 28, $32.1 billion matured.

In total, $48.7 billion in Treasuries matured. The Fed replaced $36.7 billion of them with new Treasuries via the special arrangement it has with the Treasury Department. This cuts out the middlemen on Wall Street. So these $36.7 billion in securities were "rolled over."

But the Fed did not replace the remaining $12 billion of Treasuries that matured. Instead, the Treasury Department redeemed them at face value (paid the Fed for them). In the jargon, these securities were allowed to "roll off." The blue arrow in the chart above shows this February move.

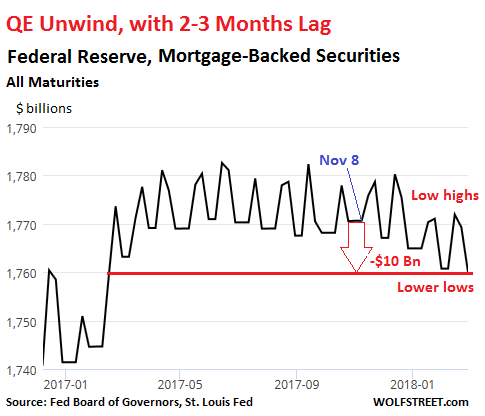

MBS are a jagged animal.

For February, the plan calls for allowing $8 billion in MBS to roll off. So how did it go?

Residential MBS differ from regular bonds. The MBS holder receives principal payments continuously as the underlying mortgages are paid down or paid off, and the principal shrinks until the maturity date, when the remainder is paid off. To keep the MBS balance steady, the New York Fed's Open Market Operations (OMO) continually buys MBS. Settlement occurs two to three months later.

This timing difference causes large weekly fluctuations in MBS on the Fed's balance sheet. It also delays the day when MBS that have been allowed to "roll off" actually disappear from the balance sheet [I explained this in greater detail a month ago here].

As a result, to determine if the QE Unwind is taking place with MBS, we're looking for lower highs and lower lows on a very jagged line. Also today's movements reflect MBS that rolled off two to three months ago, so November and December, when about $4 billion in MBS were supposed to roll off per month.

The chart below shows that jagged line. Note the lower highs and lower lows over the past few months. Given the delay of two to three months, the first roll-offs would have shown up in early December at the earliest. At the low in early November, the Fed held $1,770.1 billion in MBS. On today's balance sheet, also the low point in the chart, the Fed shows $1,759.9 billion. From low to low, the balance dropped by $10.2 billion, reflecting trades in November and December:

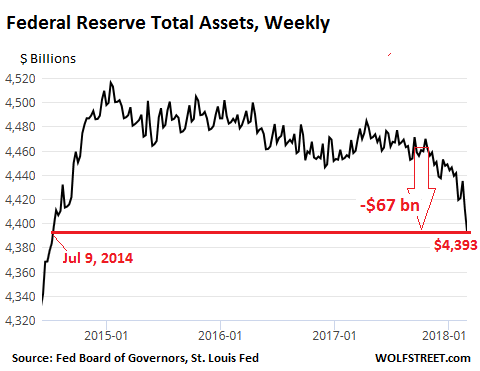

And the overall balance sheet?

Total assets on the Fed's balance sheet dropped from $4,460 billion at the outset of the QE Unwind in early October to $4,393 billion on today's balance sheet, the lowest since July 9, 2014. A $67-billion drop:

The balance sheet shows the effects not only of QE but also of the Fed's other roles that impact its assets and liabilities. The most significant among these roles is that the Fed is also the official bank of the US government. And the Treasury Department's huge and volatile cash balances are kept on deposit at the Fed. The Fed also holds "Foreign Official Deposits" by other central banks and government entities. But these activities have nothing to do with QE or the QE-Unwind.

There have been suggestions that the Fed "backed off" or "reversed" the QE-Unwind during the recent sell-off to prop up the markets. This was deducted from a single bounce in the overall balance sheet in week ending February 14. But this bounce was just part of the typical ups and downs and perfectly within range.

I have to disappoint these folks: based on what has happened in February with the Fed's Treasury securities and MBS – the only two accounts that matter for the QE Unwind: The Fed didn't miss a beat. The QE-Unwind proceeded as planned throughout the sell-off. And I expect this to continue.

This Fed isn't going to try to bail out every whiner on Wall Street. It has been clear about that. It won't take Wall-Street whining seriously until credit starts freezing up – and the credit markets are far away from that.

The housing market shudders. Could it be the new tax law and sky-high home prices?