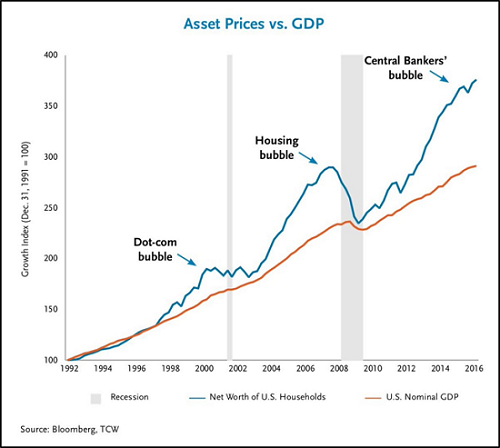

Valuations in asset markets are "frothy" and investors are basking in the "light and warmth" of the "Goldilocks economy", believing that nothing can upset a future of "sustained growth and low interest rates". We observe a heavy dose sarcasm from the media briefing coinciding with the Bank for International Settlements' (BIS) latest quarterly review. Specifically, we wonder why is it always the BIS which warns its central bank members and investors about the risk of an approaching financial crisis…and why do most of them never listen. We're not sure,but here we go again, with the BIS warning that conditions are similar to those before the crisis.

As The Guardian reports:

Investors are ignoring warning signs that financial markets could be overheating and consumer debts are rising to unsustainable levels, the global body for central banks has warned in its quarterly financial health check. The Bank for International Settlements (BIS) said the situation in the global economy was similar to the pre-2008 crash era when investors, seeking high returns, borrowed heavily to invest in risky assets, despite moves by central banks to tighten access to credit.

The BIS was one of the few organisations to warn during 2006 and 2007 about the unstable levels of bank lending on risky assets such as the US subprime mortgages that eventually led to the Lehman Brothers crash and the financial crisis.

During the media briefing, Claudio Borio, Head of the Monetary and Economic Department at the BIS, remarked how the "feel good" conditions in the markets continued in the latest quarter, while risk on "intensified".

It is as if time had stood still. Financial market participants had basked in the light and warmth of their "Goldilocks economy" in the previous quarter. They continued to do so in the most recent one. The macroeconomic backdrop brightened further. The expansion broadened and gained momentum. Above all, despite vanishing economic slack, inflation - central banks' lodestar - generally remained remarkably subdued. Nothing, it seemed, could upset a future of sustained growth and low interest rates. Accordingly, sovereign benchmark yields in core markets largely moved sideways.

The risk-on phase intensified. Headline equity market indices approached or surpassed previous peaks. Before the jitters towards the end of the period, corporate spreads narrowed further, with the US high-yield index flirting with levels not seen since the run-up to the 1998 Long-Term Capital Management crisis and, later, to the Great Financial Crisis (GFC). Emerging market economy (EME) sovereign spreads followed a similar, if less extreme, pattern, while credit default swaps - a proxy for EME sovereigns' insurance cost - reached new post-GFC troughs. As capital inflows into EMEs persisted, albeit at a diminished pace, markets remained unusually receptive to issuance from marginal borrowers. In the background, implied volatility across asset classes - equities, fixed income and currencies - if anything, sank further. Indeed, equity and bond yield volatility touched the all-time troughs previously reached briefly in mid-2014 and before the GFC; currency volatility was approaching similar lows.

What's really puzzling Claudio Borio, however, is that the market euphoria, or "ebullience" as he terms it, has continued as the Federal Reserve has proceeded with its tightening. While Borio acknowledges the BoJ has left its accommodative policy unchanged and the ECB may have "at least relative to expectations", he notes that the Fed is the "issuer of the dominant international currency and its sway on markets remains unparalleled". In Borio's view this has led to a paradox, as he explained.

Hence a paradox. Even as the Fed has proceeded with its tightening, overall financial conditions have eased. For instance, a standard indicator of such conditions, which combines information from various asset classes, points to an overall easing regardless of the precise date at which the tightening is assumed to have started. Indeed, that indicator touched a 24-year low. If financial conditions are the main transmission channel for tighter policy, has policy, in effect, been tightened at all?

However, we have been here before in the 2000s and that didn't end well. Here is Borio's take on the similarities.

In fact, this paradoxical outcome is not entirely new…it is reminiscent of the Fed policy tightening in the 2000s - the phase that spawned the now famous "Greenspan conundrum". Then overall financial conditions hardly budged, and in some respects eased, as the Federal Reserve progressively raised rates. The experience contrasted sharply with previous tightenings, not least the one in 1994. At that time, long-term rates soared, the yield curve steepened, asset prices fell, corporate spreads widened and EMEs came under pressure.

To put it simply, why does tightening lead to easing? Borio doesn't know but speculates that it lies with the macroeconomic backdrop and investor psychology. In particular, the global economy is expanding and inflation is low. It might be even worse this time because many financial market participants are expecting a "future of even lower interest rates" and inflation rates lower than the "central bank has communicated".

Borio also has another explanation, which we find particularly thought-provoking. In simple terms, because central banks now go to such lengths to be predictable and gradual in policy implementation, financial market participants have responded by taking more leverage/risk.

Less appreciated perhaps, the very mix of gradualism and predictability may also have played a role. The pace of tightening has slowed across episodes, and it is now expected to be the slowest on record. And, scorched by the outsize reaction in 1994 - not to mention the "taper tantrum" in 2013 - the central bank has made every effort to prepare markets and to indicate that it will continue to move slowly. Indeed, today's experience is reminiscent of the repeated reassurance of the 2000s' "measured pace", except that the adjustment has been, if anything, even more telegraphed. If gradualism comforts market participants that tighter policy will not derail the economy or upset asset markets, predictability compresses risk premia. This can foster higher leverage and risk-taking. By the same token, any sense that central banks will not remain on the sidelines should market tensions arise simply reinforces those incentives. Against this backdrop, easier financial conditions look less surprising.

Borio finishes with a warning about the vulnerabilities in the system, including "frothy" valuations, and how central banks might have to reconsider their gradual and predictable strategies, since they are having precisely the opposite effect to what is intended.

First, and most obvious, the jury is still out. There is a sense in which the tightening has not really begun. The vulnerabilities that have built around the globe during the unusually long period of unusually low interest rates have not gone away. As underlined in this Quarterly Review's special features, high debt levels, in both domestic and foreign currency, are still there. And so are frothy valuations, in turn underpinned by low government bond yields - the benchmark for the pricing of all assets. What's more, the longer the risk-taking continues, the higher the underlying balance sheet exposures may become. Short-run calm comes at the expense of possible long-run turbulence.

Second, a deeper question is what defines an effective tightening. Can a tightening be considered effective if financial conditions unambiguously ease? And, if the answer is "no", what should central banks do? In an era in which gradualism and predictability are becoming the norm, these questions are likely to grow more pressing.

In the run-up to the last crisis, it was the BIS's then head of the Monetary and Economic Department, William White, who "rang the bell", now his successor is doing the same. White is currently chairman of the Economic and Development Review Committee at the OECD and, as we noted in the past months, is warning his new organisation sees "more dangers" today than in 2007.