Thursday afternoon, the Fed released its weekly

balance sheet for the week ending November 1. This completes the first

month

of the QE unwind, or "balance sheet

normalization," as the Fed

calls it. But curious things are happening on the

Fed's balance sheet. On September 20, the Fed announced that the QE unwind would begin October 1, at the

pace announced at its June 14 meeting. This would shrink the Fed's balance

sheet by $10 billion a month for each of the first three months. The

shrinkage would then accelerate every three months. A year from

now, the shrinkage would reach $50 billion a month – a rate of $600 billion

a year – and continue at that pace. This would gradually destroy some of the

trillions that had been created out of nothing during QE. Over the five

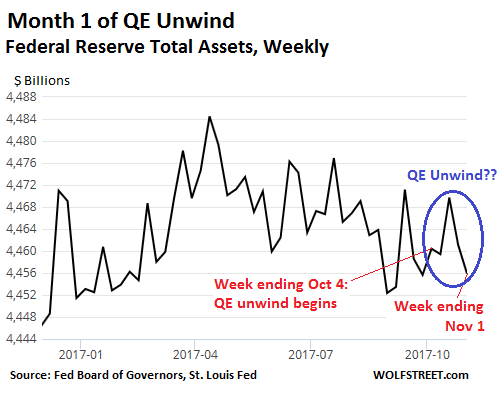

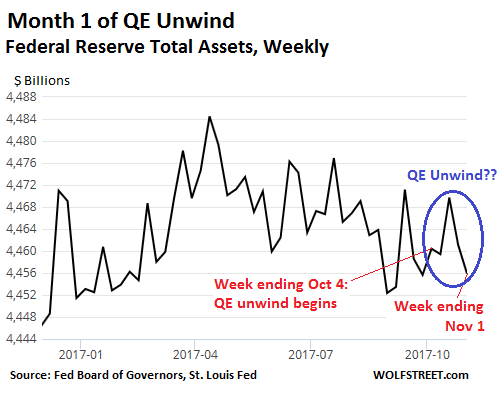

weekly balance sheets since the QE-unwind kick-off date, total assets rose

initially by $10 billion from October 4 to October 18 and then fell by $14

billion, for a net decline of $4 billion. By November 1, total assets were $4,456

billion:

The Fed is supposed to unload $10 billion in October.

Instead it unloaded $4 billion. And the variations from week to week are

entirely in the normal range of the prior months.

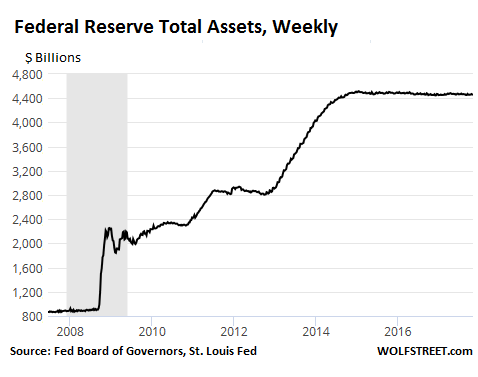

The chart below shows the Fed's total assets since

2007, covering the entire QE period from the Financial Crisis on. The tiny

$4-billion decline in October gets lost in the massive table mountain of

assets:

BBut a first real

step has happened.

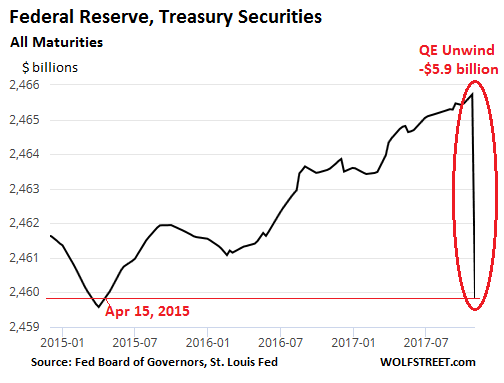

As part of the $10 billion that the Fed said it would

shrink its balance sheet in October, it was supposed to unload $6 billion in

Treasury securities.

The way the Fed undertakes the balance sheet

normalization is not by selling Treasury securities outright but by allowing

them, when they mature, to "roll off" the balance sheet. In order

words, when they mature, the Treasury Department pays the Fed the face value of

those securities. Then, instead of reinvesting the money in new Treasuries, the

Fed destroys the money. This is the opposite of what it had done during QE when

it created the money to buy securities.

On October 31, $8.5 billion of Treasuries that the Fed

had been holding matured. If the Fed stuck to its announcement, it would have

reinvested $2.5 billion and let $6 billion (the cap for the month of October)

"roll off." The amount of Treasuries on the balance sheet should then

have decreased by $6 billion.

And that's what happened. This chart of the Fed's

Treasury holdings shows that the balance dropped by $5.9 billion, from an

all-time record 2,465.7 billion on October 25 to $2,459.8 billion on November

1, the lowest since April 15, 2015:

So the QE unwind of Treasury securities has commenced.

But

mortgage-backed securities?

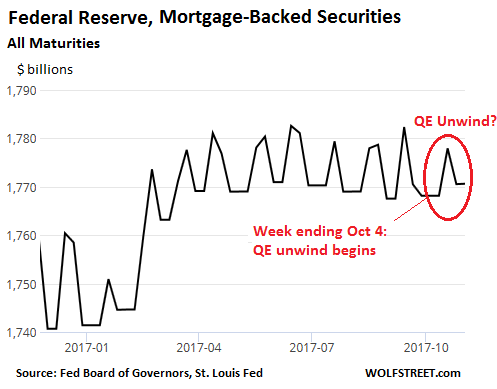

As part of the $10 billion unwind in October, the Fed

was also supposed to unload $4 billion in mortgage-backed securities (MBS). How

did that go so far?

On October 4, it held $1,768.2 billion in mortgage

backed securities. On October 18, this spiked by nearly $10 billion to $1,777.9

billion. Since then, it has fallen by $7.3 billion to $1,770.6 billion, but

remains $2.4 billion higher than at the outset of the QE unwind:

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento