The hot topic in monetary economics today (hah, if it's not an oxymoron to say these terms together!) is whither interest rates. The Fed in its recent statement said the risk is balanced (the debunked notion of a tradeoff between unemployment and rising consumer prices should have been tossed on the ash heap of history in the 1970's). The gold community certainly expects rapidly rising prices, and hence gold to go up, of course.

Will interest rates rise? We don't think it's so obvious. Before we discuss this, we want to make a few observations. Rates have been falling for well over three decades. During that time, there have been many corrections (i.e. countertrend moves, where rates rose a bit before falling even further). Each of those corrections was viewed by many at the time as a trend change.

They had good reason to think so (if the mainstream theory can be called good reasoning). Armed with the Quantity Theory of Money, they thought that rising quantity of dollars causes rising prices. And as all know, rising prices cause rising inflation expectations. And if people expect inflation to rise, they will demand higher interest rates to compensate them for it.

The quantity of dollars certainly rose during all those years (with some little dips along the way). Yet the rate of increase of prices slowed. Nowadays, the Fed is struggling to get a 2% increase and that's with all the "help" they get from tax and regulatory policies, which drive up costs to consumers but has nothing to do with monetary policy. Nevertheless interest rates fell. And fell and fell.

Why Have Interest Rates Been Falling?

It seems obvious that if one wishes to say that a trend has changed, after enduring for well over three decades, one needs to explain why. The Question of the Day is: what has suddenly happened? The quantity of dollars is going to rise? Been there done that, got the falling interest T-shirt. Prices are going to rise? Maybe.

For extra credit, no scratch that, to get any credit your answer should include an explanation of why the rate has been falling for so long. Is this too much to ask? Your explanation should contain three parts:

- The cause that drove interest rates to fall for most of the time that Generation X has been alive, for most of the duration of the careers of even the oldest Baby Boomers

- Why the old cause is now inoperable

- Identify a new cause, and show why it will drive the new trend for rising rates

Keith published his theory of interest and prices. To cut to the chase, interest falls when the rate is above the marginal productivity of the entrepreneur. That is, when the marginal entrepreneur earns a lower return on capital than he must pay for the credit to finance it.

It should be obvious that you cannot borrow at 10% to earn 8%. If this is happening to the true marginal entrepreneur, and not just to an isolated bad businessman, then the interest rate must fall. It must fall because business demand for credit is weak under such conditions. And if the rate rises, the demand gets even softer. Businesses who can repay their debts will do so, even if they must liquidate capital assets to do so. Certainly, new businesses will not enter the market if they see a negative spread between cost of capital and return on capital.

Only when the rate falls, do businesses demand credit. When the rate falls, from say 10% to 7%, they can then make a positive spread.

Unfortunately, the drop in rates does not rectify the problem. Our hapless entrepreneur may have sold bonds into the market at 10%. And now he's stuck with that rate.

Even if not, he is locked into his capital assets, such as building and equipment. Consider the marginal restaurateur. Let's call him Fred. When rates were high, he was very careful to borrow as little as possible to buy and remodel a building into a suitable environment to serve high-end food. But then rates drop, and another guy can borrow more to open a more opulent restaurant next door. Diners willing to pay $100 a plate may be attracted to the new place, and reluctant to eat at Fred's. So Fred must lower his price. Sure, he may be paying only 7% now. But he cannot command the same price, and hence earn the same gross margin.

Or consider the marginal manufacturer, Barney. He stamps and welds metal frames for trailers. He set up shop when the interest rate was 10%, so half a million dollars of equipment was a lot for his business to support. However, years later when interest is 5%, a new entrant can put a million dollars into computer-controlled machines plus an automated line. This new company incurs a lower cost to put out the same product. Barney struggles to compete.

Profits Follow Rates

Profit margins follow interest rates.

Notice that this dynamic looks a lot like the bogus view of government-managed "perfect competition". Businesses struggle to make decent margins. Then margins fall, with the government relentlessly turning up the pressure. This process goes on for decades, fueling quite a consumer boom, as firms are put onto a treadmill turning faster and faster, forced to lower prices and to borrow to invest more and more in technology and in capital such as tooling. Every year, smart phones get smarter, big screen TVs get bigger, and sports cars get more sporting.

It's all lots of fun. The dirigiste-technocrats claim credit for managing the economy to the benefit of consumers. Meanwhile, the free marketers say "see, look at the benefits of capitalism!" They're both wrong. It's certainly not capitalism, and since consumers are also workers, savers, and owners of capital, they do not benefit from a wholesale conversion of wealth into income. To paraphrase (with some liberties) economist Ludwig von Mises, Keynes did not teach stone-headed central planners to turn water into wine, but to direct us to the not-so-miraculous eating of the seed corn.

Do the revelers benefit from the eating of the seeds that they would plant in order to eat next year?

A boom is not a healthy economy. Falling interest rate induced churn is not creative destruction. And the economy is not driven by consumption.

Anyways, the falling rate, falling margins, and hence falling return on capital is a ratchet. A drop in interest rates does not rectify it, only drives it down further.

This is our answer to part 1 of the Question of the Day. The cause is interest > productivity.

However, we do not agree that this cause has become inoperable. We believe it is still in full force and effect.

Zombie Firms

The Bank for International Settlements defines a zombie corporation as being unable to pay its interest expense from its profits. Sound familiar?

A zombie can only exist by the grace of too-low interest rates, and a very permissive credit environment. In other words, they (we) can thank central banks for these resource-sucking, wealth-destroying, boat anchors on the economy. Oh and let's not forget worker-underpaying in our litany of the flaws of zombies.

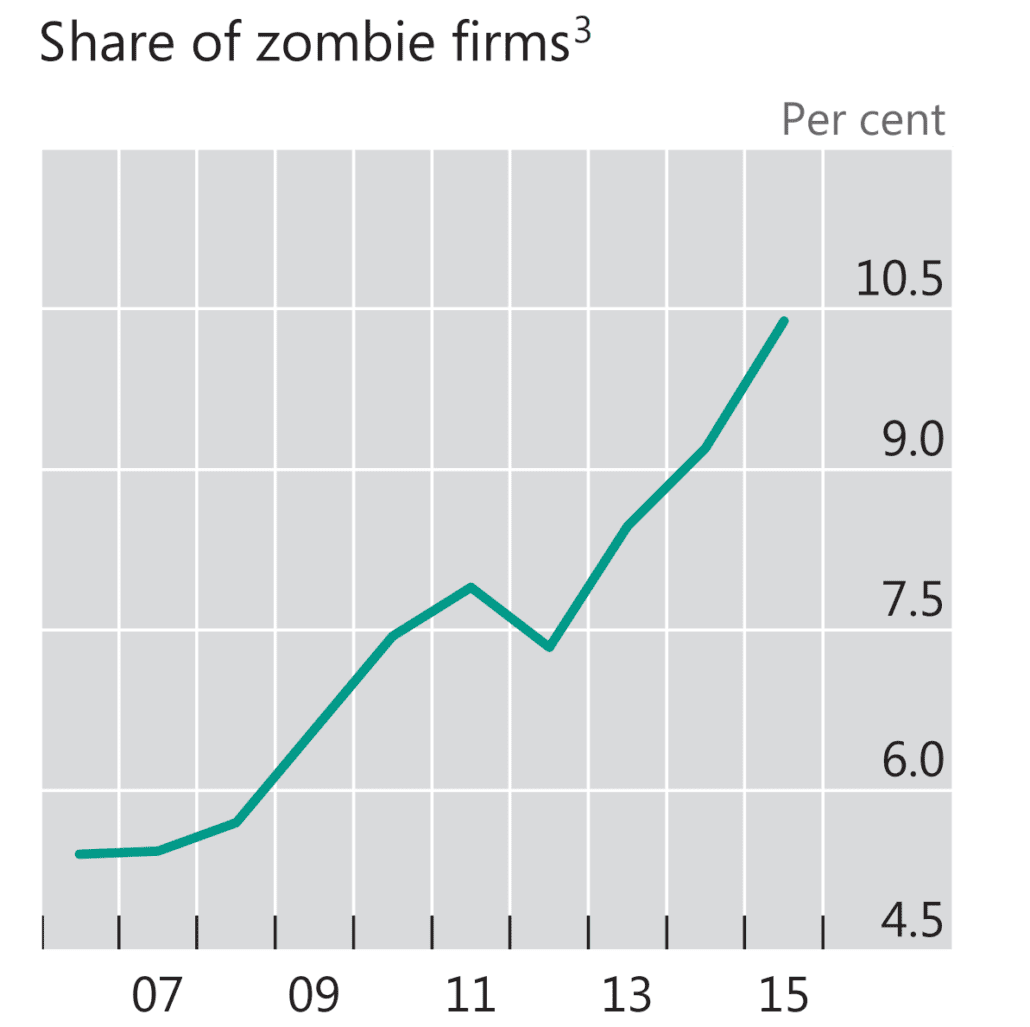

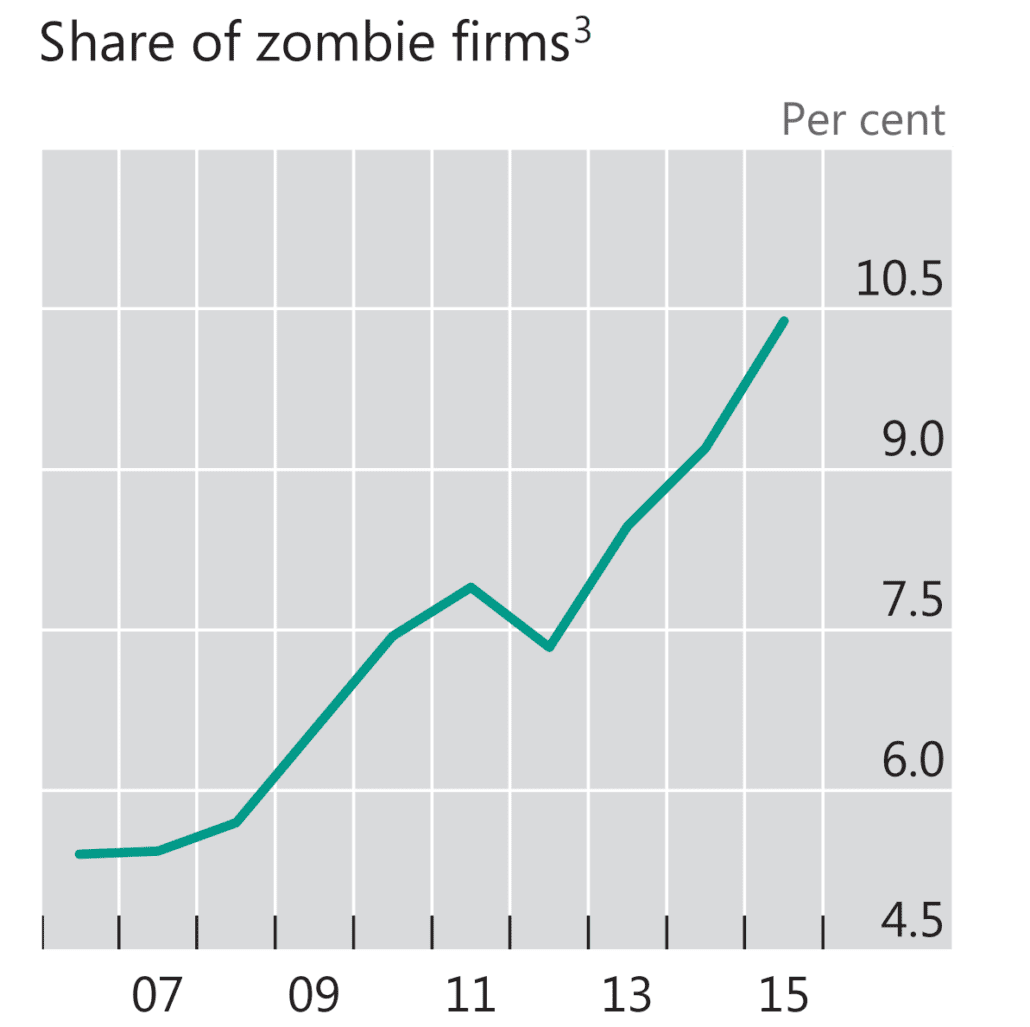

Here is a graph, taken from the BIS 87th Annual Report, showing the growth of the zombiehorde over the past decade or so.

3 Zombie firms are defined as listed firms with a ratio of earnings before interest and taxes to interest expenses below one, with the firm aged 10 years or more. Shown is the median share across AU, BE, CA, CH, DE, DK, ES, FR, GB, IT, JP, NL, SE and US.

This graph ends in 2015, though we note that the trend is sharply rising. From about 5% before the global financial crisis, the percentage of zombies more than doubled. What is it up to by now?

This is a picture of a problem that has grown beyond merely the marginal enterprise. It is a significant fraction of the global economy!

What will happen to these companies' demand for credit as rates rise? One anecdote is Ford. In February, we noted that the automakers are still offering to finance their cars at 0% for 72 months. However, their cost of capital has been rising. We used this in another angle looking at the soft demand for credit as rates rise. Ford knew that sales would drop if it tried to pass through the interest rate increase to its customers. Ford determined that the loss of profitability due to this sales drop would be greater than its cost to keep subsidizing 0% financing. We did some rough back-of-the-envelope math to estimate Ford's increase in costs (not its total cost, just the increase due to the rise in rates since 2014) to be about $1.4 billion. Ford's annual profit is about $5 billion, so this has eaten about 28% of its net profit.

The postscript is that Ford has recently announced that it will stop making cars except the Mustang sports car, and Focus crossover. It will focus on trucks, which have higher margins. Margins for trucks and SUVs may be fat enough to support the finance subsidy, for now.

Ford, of course, is a big name. Out of the spotlight and away from press coverage, many other businesses are reducing their demand for credit in response to the rise in rates. With falling demand, the price of credit cannot rise far or durably.

This analysis is aside from the political reality that every interest group, and every politician from the president on down, will be pressuring the Fed to lower rates to avoid the bankruptcies of 10.5% (more, by now) of corporations, the layoffs of their workforces, the losses to banks, insurers, and pensions on the bonds of these corporations, the loss of tax revenues to federal, state, and local governments, the burgeoning welfare budgets, the embarrassing hit to economics statistics like GDP and unemployment, etc.

We are painting a picture of dropping credit demand as its cost rises. And the demand will drop even more if those bankruptcies and layoffs occur. Unemployed people do not buy new Ford trucks, even if Ford gives them 0% financing for 72 months.

Next week, we will give our answers to parts 2 and 3 of the Question of the Day. They are hypothetical answers, as we have shown interest is above marginal productivity—with a vengeance. So we will look at what it would take to reverse this ratchet.

Supply and Demand Fundamentals

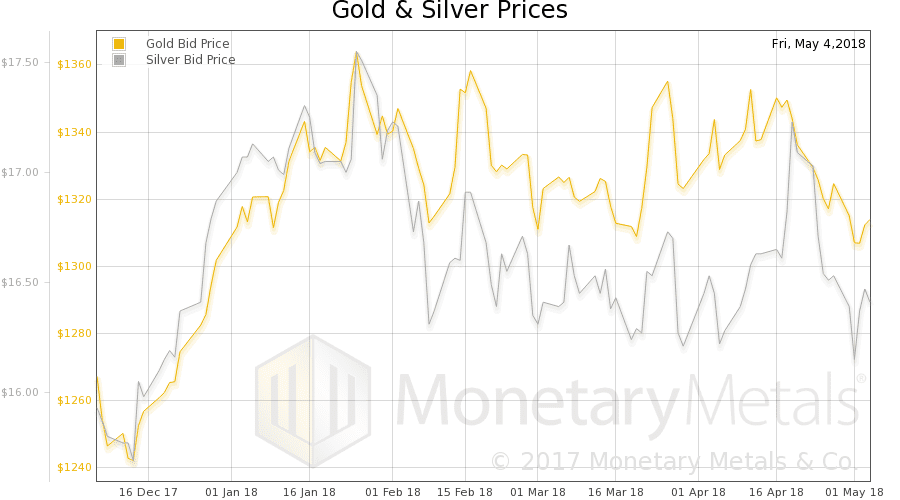

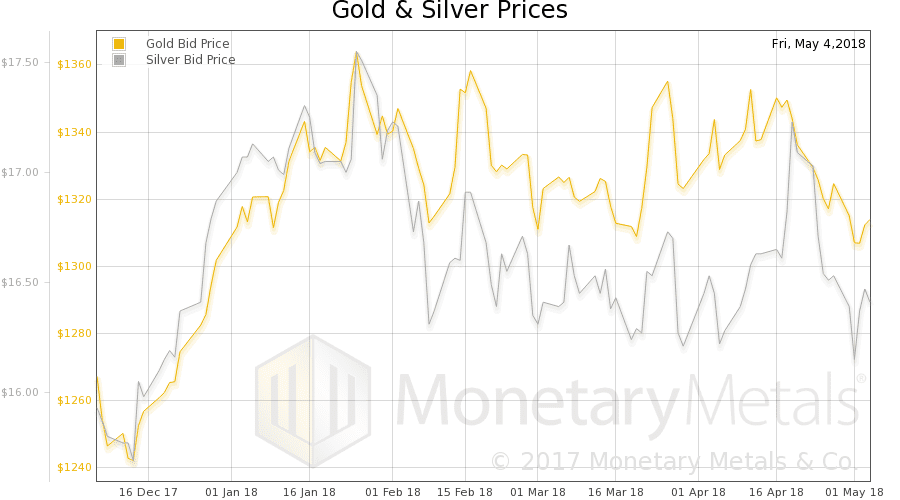

The price of gold dropped 9 bucks, while that of silver rose 3 cents.

Readers often ask us if permanent backwardation (when gold withdraws its bid on the dollar) is still coming. We say it is certain (unless we can avert it by offering interest on gold at large scale). They ask is it imminent, and we think this is with a mixture of fear and longing for a higher gold price. We say well yeah that will bring a much higher gold price (perhaps it will hit some of the gold bug predictions, or perhaps it will go off the board before getting that high) but be careful what you wish for. And it's not imminent. We will have a graph below that gives it some perspective.

In the meantime, we all watch the price of gold and maybe trade it when there's a clear opportunity.

Speaking of which, we will show the only true picture of the fundamentals of supply and demand in gold. But first, here is the chart of the prices of gold and silver.

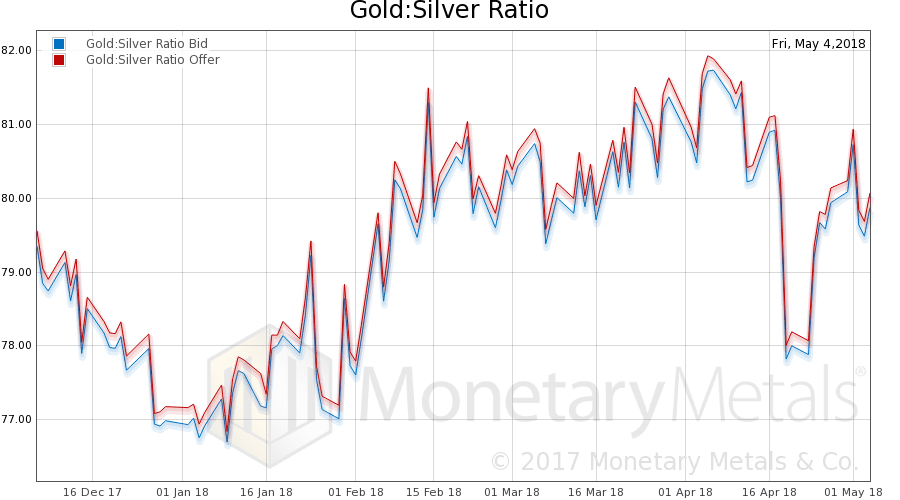

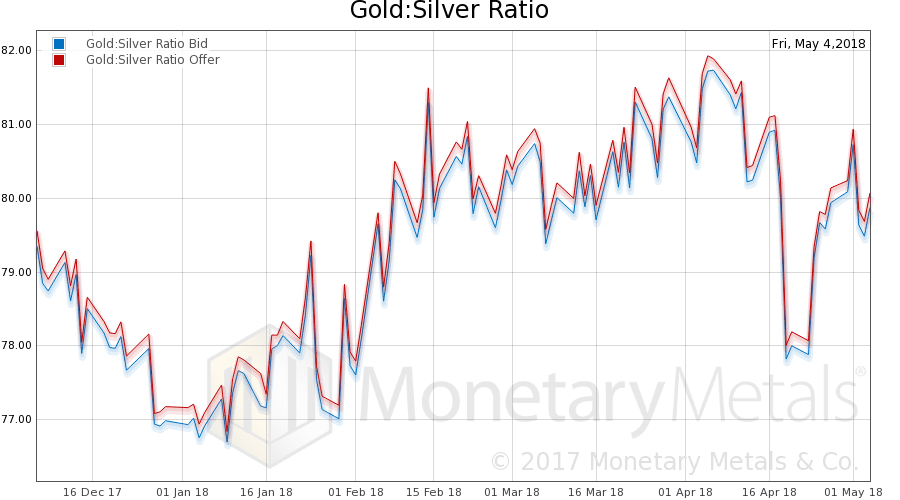

Next, this is a graph of the gold price measured in silver, otherwise known as the gold to silver ratio (see here for an explanation of bid and offer prices for the ratio). It fell this week.

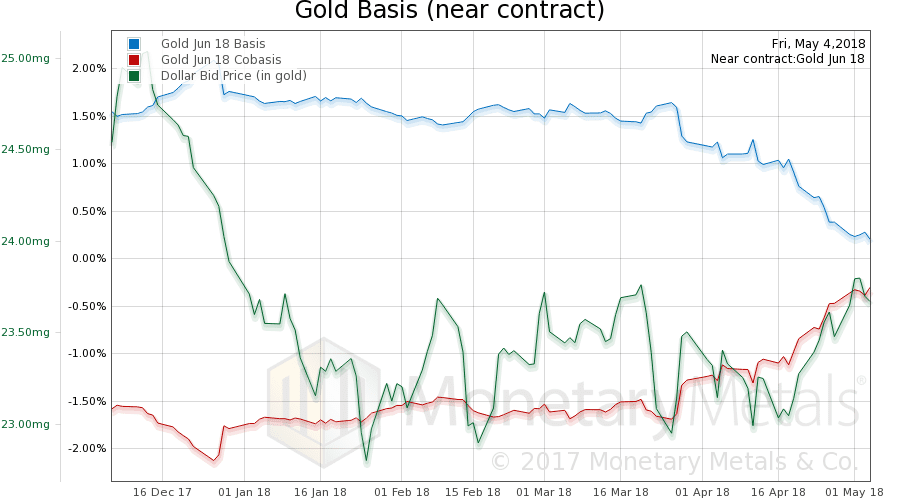

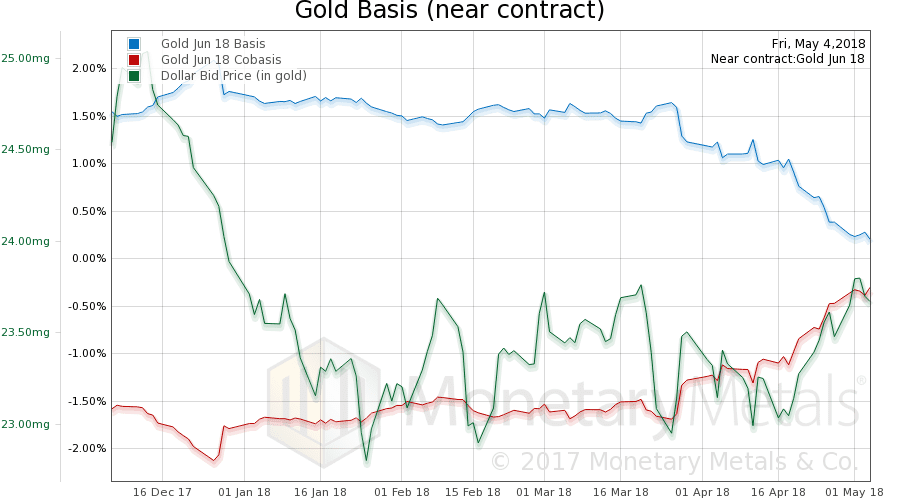

Here is the gold graph showing gold basis, cobasis and the price of the dollar in terms of gold price.

The price of gold fell slightly (which means the dollar rose, as measured in gold). And with the price drop comes an increase in scarcity (i.e. the cobasis, the red line). Alas, this is just the near contract which is already under selling pressure as it expires in a few weeks. Farther contracts do not show an increase in scarcity, but a slight decrease (not a sign of imminent backwardation).

Here is a graph of the gold term structure. Note no backwardation, and each farther contract has a higher basis (which is normal).

The Monetary Metals Gold Fundamental Price fell $41 this week to $1,497. Now let's look at silver.

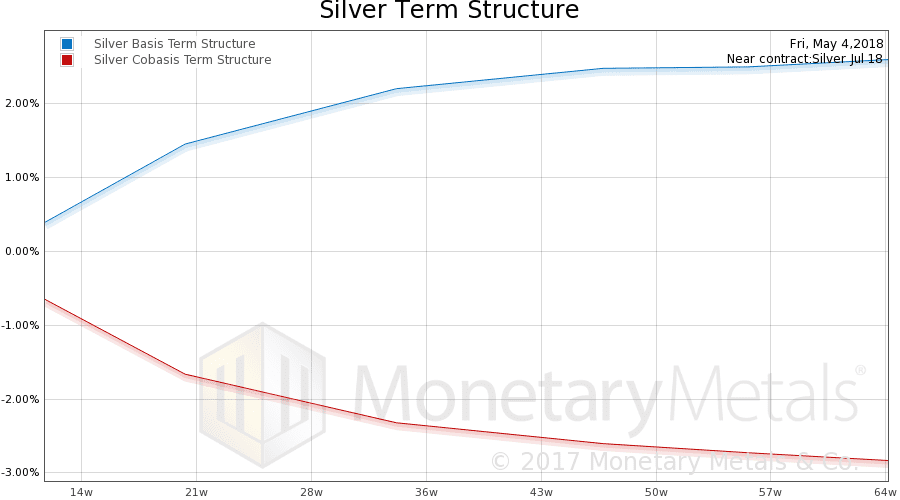

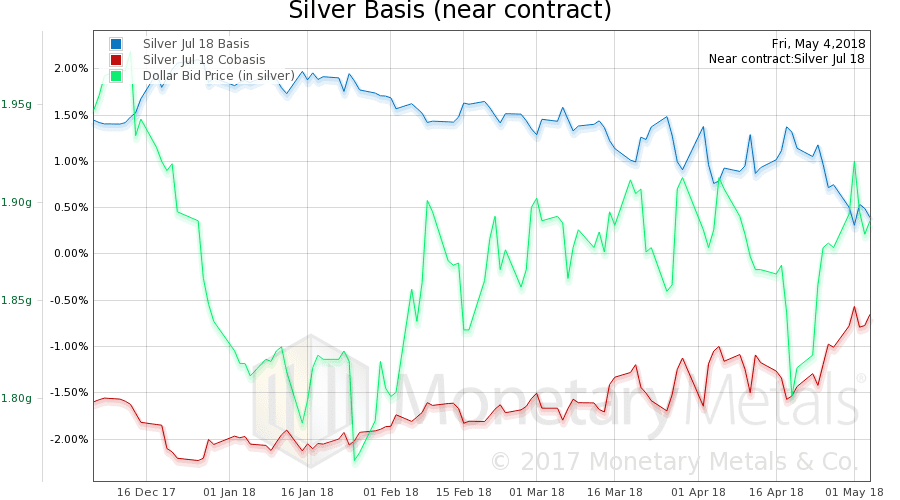

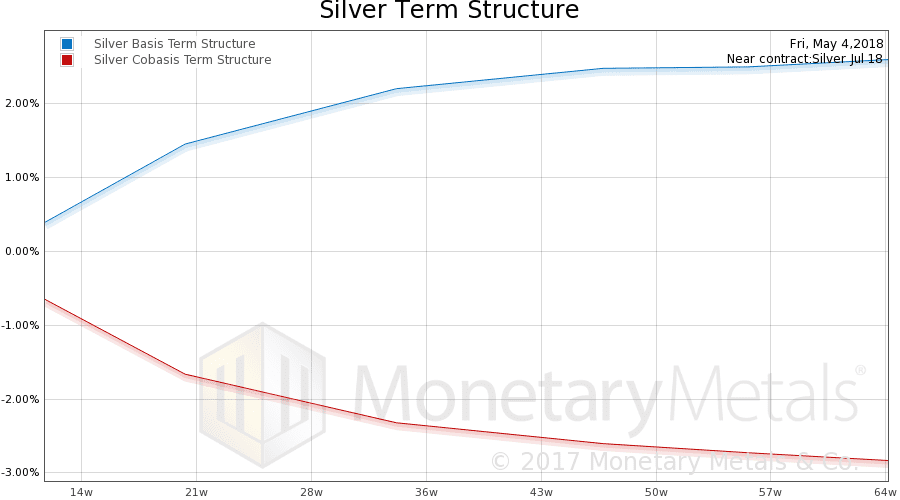

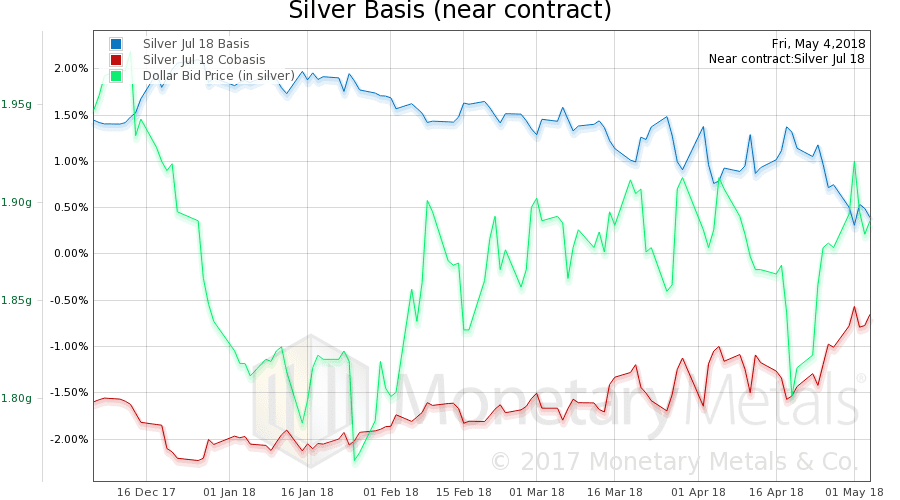

In silver, not only did the price rise (a few pennies) but scarcity increase in the near and farther contracts. So it should not be a surprise that the Monetary Metals Silver Fundamental Price rose 20 cents to $17.69.

Here is a graph of the silver term structure.