Has anything actually changed in the past two weeks? The conventional bullish answer is no, nothing's changed; the global economy is growing virtually everywhere, inflation is near-zero, credit is abundant, commodities will remain cheap for the foreseeable future, assets are not in bubbles, and the global financial system is in a state of sustainable wonderfulness.

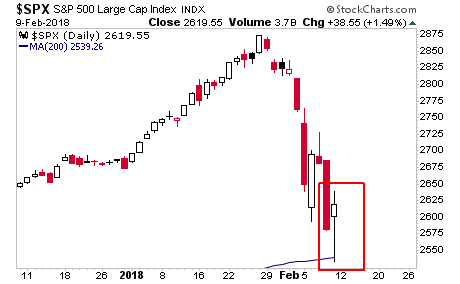

As for that spot of bother, the recent 10% decline in stocks: ho-hum, nothing to see here, just a typical "healthy correction" in a never-ending bull market, the result of flawed volatility instruments and too many punters picking up dimes in front of the steamroller.

Now that's winding up, we can get back to "creating wealth" by buying assets--$2 million homes in Seattle that were $500,000 homes a few years ago, stocks, bonds, private islands, offshore wealth funds, bat guano, you name it. Just borrow whatever you need to borrow to buy more.

(But don't buy bitcoin. No no no, a thousand times no. It is going to zero, Goldman Sachs guaranteed it.)

Ahem. And then there's reality: something has changed, something important. What changed? The endlessly compelling notion that risk has magically vanished as the result of financial sorcery is now in doubt. If risk hasn't been made to disappear, and even worse, can't be corralled into a shortable instrument like VIX, then--gasp--every asset and instrument might actually be exposed to some risk.

As I've noted many times here, risk cannot be made to disappear; it can only be transferred onto others or off-loaded into the financial system itself. Risk can be cloaked or masked, and indeed, that is the beating heart of financial alchemy: we can eliminate risk by hedging via exotic instruments.

Once risk has been vanquished, then we can safely invest in all sorts of high-yield ventures that were once risky: junk bonds, emerging market debt, private wealth funds and so on.

But if risk cannot be destroyed, then where is it? If we can locate and isolate it, then we can hedge it, right?

But what if risk has been pushed into the vast machinery of the global financial system itself? This was the unwelcome (and as yet unlearned) lesson of the 2007-08 Global Financial Meltdown: risk, we were told, was confined to the subprime mortgage corral, and if you avoided that corral, your exposure to risk was near-zero.

That turned out to be false. The belief that risk exposure is near-zero generates an irresistable desire to load up on high-yield riskier assets because, hey, why not? If risk is near-zero, why leave all that low-hanging fruit on the tree?

This is a self-reinforcing feedback loop: the higher the yields available on risk assets, and the lower the perceived risk exposure, the greater the incentives to move more borrowed money into ever-riskier assets, which then pushes systemic risk ever higher.

The end-game of this self-reinforcing feedback loop is collapse, as risk inevitably emerges where it is least expected. Home mortgages were safe and boring. Well, not quite, after financial alchemy was applied to vanquish risk and thus unleash enormously profitable financialization.

Nobody knows where systemic risk might emerge, or how much risk exposure is lurking in assets. What was once safe is now less certainly safe. So where do you earn those fat returns without risk, the returns the world has come to see as entitlements due capital everywhere, at all times?

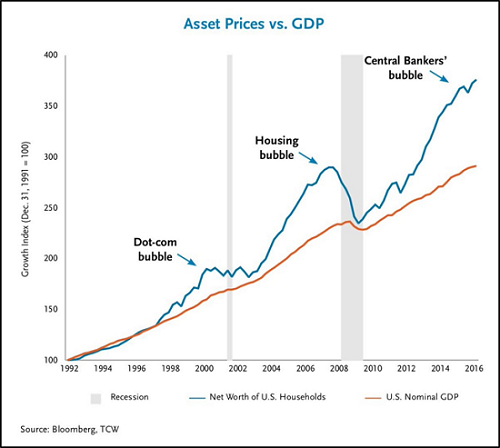

The illusion that risk can be limited delivered three asset bubbles in less than 20 years.Each bubble collapse caused more structural damage, and each central bank "save" introduced higher levels of systemic fragility, which is another way of saying systemic risk.

Though no one in the financial sector dares say this in public, the possibility that central banks can no longer sustain the illusion that risk has been vanquished is now front and center. If risk can't be corralled and quantified, then it can't be offset with any degree of confidence. If risk can't be corralled and quantified, it can't be offloaded onto unsuspecting others without the possibility that the system itself will collapse once the risk that's been piling up in the global machinery manifests.

Something has changed, but nobody dares talk about it. That tells those who listen to what's not being said something of great value.